The Old Nichol, also known as the Nichol or the Old Nichol Street Rookery, was an area of housing in the East End of London. The slum was located in the western boundary of Bethnal Green, with six of its streets across Boundary Street located in Shoreditch.[2] The Old Nichol was home to 5,719 people, living in a dense network of about 30 streets and courts. The late 18th-century houses included workshops and stables.[3]

In Victorian Britain of the 1880s, the Old Nichol was London’s most notorious slum.[3] The “evil” reputation of the Old Nichol owed much to Arthur Morrison’s fictionalised account of it in A Child of the Jago (1896), and to sensational articles by Rev. Osborne Jay of Holy Trinity Church, known as Father Jay, on whom Morrison relied for information.[4]

With the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s, the garden and fields on the land that became the Old Nichol passed into private hands. The Preston Gardens were created on what would later become the southernmost part of the Old Nichol, and the Swan Field would become Mount Street, today's Swansfield Street. Crock Lane, later Boundary Street and Church Street, was established in an L-shape, with narrow alleys running from it, established the original topographical characteristics of the Old Nichol. In the 1670s City of London merchants and lawyers started buying small freeholds behind St Leonard's, Shoreditch.

The Gray's Inn lawyer John Nichol bought nearly five acres of land, bounded by the two arms of Cock Lane, on which he built seven houses. In 1680 he leased the land to Jon Richardson, a mason, who dug clay for brick-making during the London Restoration-era building boom, and then sublet his land to builders who constructed houses on the land. In the 1680s and 1690s Nichol Street, later Old Nichol Street, was developed, with Nichol Row being added in 1703, New Nichol Street between 1705 and 1708, and later Half Nichol Street.[5] A high number of the 25,000 Protestant Huguenots who arrived from France in the late 1680s and 1690s and settled in Spitalfields and south Bethnal Green were silk weavers. This led to many houses in the north of the Old Nichol featuring "long lights", also known as weaver windows, so as to maximise daylight in the upper storey of the house where handloom weavers worked. Virginia Row, Virginia Road and (Old) Castle Street were built in the 1680s, while Mount Street and Rose Street existed by 1725. Until the 19th century, when the Old Nichol was established, the area between Mount Street, Rose Street and Half Nichol Street was fields. Late 17th-century housing was eventually demolished and speculative new building created Nelson, Vincent, Collingwood, Trafalgar, Mead, Christopher and Sarah Street, with numerous courts in between.[6] In the 1870s the street names in the north of the Old Nichol were changed in order to protect the memory of Admiral Nelson, in whose honour the streets had been named, from negative association.

The Gray's Inn lawyer John Nichol bought nearly five acres of land, bounded by the two arms of Cock Lane, on which he built seven houses. In 1680 he leased the land to Jon Richardson, a mason, who dug clay for brick-making during the London Restoration-era building boom, and then sublet his land to builders who constructed houses on the land. In the 1680s and 1690s Nichol Street, later Old Nichol Street, was developed, with Nichol Row being added in 1703, New Nichol Street between 1705 and 1708, and later Half Nichol Street.[5] A high number of the 25,000 Protestant Huguenots who arrived from France in the late 1680s and 1690s and settled in Spitalfields and south Bethnal Green were silk weavers. This led to many houses in the north of the Old Nichol featuring "long lights", also known as weaver windows, so as to maximise daylight in the upper storey of the house where handloom weavers worked. Virginia Row, Virginia Road and (Old) Castle Street were built in the 1680s, while Mount Street and Rose Street existed by 1725. Until the 19th century, when the Old Nichol was established, the area between Mount Street, Rose Street and Half Nichol Street was fields. Late 17th-century housing was eventually demolished and speculative new building created Nelson, Vincent, Collingwood, Trafalgar, Mead, Christopher and Sarah Street, with numerous courts in between.[6] In the 1870s the street names in the north of the Old Nichol were changed in order to protect the memory of Admiral Nelson, in whose honour the streets had been named, from negative association.

Many of the buildings in the Old Nichol contravened the Building Acts. Builders leasing land from owners who did not care what use was made of the acreage, so long as it was profitable, created an instant slum. The use of cheaper lime-based substances derived from the by-products of soap-making at local factories was the most important factor in the swift deterioration of the building fabric in the Old Nichol. Speculative builders used this cement, which was known as "Billysweet", instead of traditional lime mortar, and it quickly became infamous for never thoroughly drying out, leading to sagging and unstable walls. Other architectural features that contributed to urban decay in the Old Nichol included the lack of foundation of most early 19th-century houses, which were built with floorboards laid on bare earth, cheap timber and half-baked bricks of ash-adulterated clay. The roofs were badly pitched, leading to rotting rafters and blooming plasterwork. The houses were permanently soggy, as damp from the roof and the earth seeped through the buildings. By 1836 the whole 15 acres (61,000 m2) of land which would form the Old Nichol had been built or rebuilt upon.[7]

Over the following fifteen years back yards and other open spaces were built upon with shanty-style developments, creating illegal courts, small houses, workshops, stables, cowsheds and donkey stalls. As surveyors and cartographers struggled to keep accurate maps of the Old Nichol, the already high population density increased further.[8] Families with more than one child often lied to be able to obtain a room and were thrown out if the rent collector or landlord found out that more than one child lived with family in one room. Monday was rent day, known as "Black Monday", and in the Old Nichol women would form queues outside the pawnshops with their belongings. The rent was collected by house agents who would evict tenants if the rent was in arrears[9] In 1863 The Builder reported of the Old Nichol that:

On 24 October 1863 The Illustrated London News published an article entitled "Dwellings of the Poor in Bethnal-Green" which described the living conditions in the Old Nichol:

The overcrowding in the Old Nichol was made worse as in the twenty years to 1887 various improvement projects were implemented. These included the widening and re-routing through slum streets of Bethnal Green Road in the late 1870s, at the southern edge of the Old Nichol, which made 800 people homeless, the creation of a large number of warehouses and factories in Shoreditch, the construction of three massive London School Board buildings within the Old Nichol, and in 1888/1889 a new church in Old Nichol Street required the eviction of 500 people.[12]

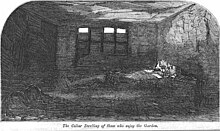

Some ten percent of the houses in Boundary Street had subterranean corridors in 1883, which the local medical officer regarded as one of the most alarming architectural phenomena of the Old Nichol housing stock. The only way to reach the back yard, in which the dustbins and the lavatory was located, was by descending rickety steps, passing through an unlit, unpaved cellar passageway just five feet high, with the yard at the other side. Cellars were illegally rented in the Old Nichol, though the law stated that underground living quarters had to have a window giving at least one foot of light at pavement level, a fireplace, drainage and head room of at least 7 ft (2.1 m).[13] On 31 October 1863 The Builder (vol. XXI, no. 1082) published an article "More Revelations of Bethnal Green", describing the underground rooms of the Old Nichol:

The Old Nichol was a Cockney enclave, with second and third generation Londoners forming the majority of inhabitants of the slum. Over a third of London's four million inhabitants had been born outside the city, but this figure dipped to an eighth in the Old Nichol, the lowest figure for any part of London. The Old Nichol, like the 129,000 inhabitants of Bethnal Green, was in the late 1880s largely homogeneous, although there was a significant number of settled and half settled Irish gypsy, known as "didikai", and Romany families, and judging from the surnames, descendants of Huguenot settlers.[12] The rotten housing stock of the Old Nichol was the only type of property the very poorest could afford. The surviving Poor Law case histories for the area show that the Old Nichol was for many East End Londoners the final stop before entering into workhouses.[14]

The Old Nichol was locally known as "The Sweaters' Hell", in references to the prevalence of home-based artisan work that paid little among Old Nichol inhabitants. Work was plentiful, but pay was poor and wages got lower. Hundreds of Old Nichol inhabitants made couches, chairs, mirrors and toys, or worked as sawyers, carvers, french polishers, ivory turners and upholsterers, with their tiny homes doubling as workshops. The Old Nichol had several timber yards and on weekdays the streets of the Old Nichol saw carts and barrows carry newly sawn planks and freshly turned furniture components. Finished tables, chairs and wardrobes were sold to the local wholesaler.[15] Close to the Old Nichol were Shoreditch's Curtain Road furniture depots and wholesale emporia. The proximity to the London Docks, which required vast amounts of casual, ill-paid labour, made the Old Nichol home to low-paid labourers. Street sellers also lived in the Old Nichol, which was ideally situated just outside the City of London boundaries, a 15-minute walk from Liverpool Street station and a 25-minute walk from the Bank, Mansion House, and Guildhall.[16]

In 1863 an article in The Illustrated London News described the living and working conditions in the Old Nichol:

Whooping cough, which killed more children under the age of five than any other transmittable illness, scarlet fever, diphtheria, measles, smallpox, bronchitis and especially tuberculosis had a fatality rate in the Nichol that was twice as high as that in Bethnal Green, at that time a very poor East London parish. While the contagion rate in the Old Nichol was not higher than in Bethnal Green, inhabitants of the Old Nichol were less likely to recover. Contemporary medical thinking linked the health statistics of the Old Nichol to the overcrowding, lack of sanitary fittings, pervasive damp, and lack of light and fresh air.[17]

In the late 1880s the annual mortality rate in the Old Nichol was 40 per 1,000 people, with Bethnal Green's being between 22 and 23 per 1,000 people, and the national average being 19 to 20 per 1,000 people. Four-fifths of the around 5,700 inhabitants of the Old Nichol were children[2] and the death rate of babies under the age of one was 252 per 1,000 live births, compared to Bethnal Green's death rate of 150 per 1,000 live births, which was in line with average death rates in England and Wales.[17] It 1887 the coroner in Bethnal Green reported that around five out of six infant deaths investigated by the coroner were found to be suffocation cases in one-room homes where the entire family had slept in one bed. The cause of deaths was described as "overlaying", with a sleeping parent or older child rolling on top of the infant and accidentally killing it. The press at the time noted that such deaths were more common on Friday, Saturday and Sunday nights, suggesting that heavy drinking was a factor in the fatalities.[18]

No comments:

Post a Comment