Feature Articles – Fairy dust: the Cottingley fairies

In 1983, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths stated that back in 1917, they had perpetrated a majestic hoax. Their world famous photographs, showing the girls in the company of fairies dancing around them, were paper cut-outs, supported by hatpins. It had fooled both sceptics and believers.

by Philip Coppens

The famous Cottingley fairies were “photographed” by two girls Elsie Wright, 15, and her cousin Frances Griffiths, 10, in the last days of the First World War. The case got its international acclaim through Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, who was fascinated by the account and published an article in the Strand Magazine in December 1920. With the world’s attention focused on them, the girls had little option but to stick to their story. A juvenile prank had grown into a mass media circus. To this day, the suburban area of Cottingley continues to get visitors and the official retraction, even though more than 20 years ago, is still not as a well-known as the hoax itself. This may be partly due to the fact that the story was put to film in 1997 under the title Photographing Fairies. Locals are asked where the Fairy Glen is, even though the site along the small river is off limits, due to the danger of erosion.

The famous Cottingley fairies were “photographed” by two girls Elsie Wright, 15, and her cousin Frances Griffiths, 10, in the last days of the First World War. The case got its international acclaim through Arthur Conan Doyle, the author of Sherlock Holmes, who was fascinated by the account and published an article in the Strand Magazine in December 1920. With the world’s attention focused on them, the girls had little option but to stick to their story. A juvenile prank had grown into a mass media circus. To this day, the suburban area of Cottingley continues to get visitors and the official retraction, even though more than 20 years ago, is still not as a well-known as the hoax itself. This may be partly due to the fact that the story was put to film in 1997 under the title Photographing Fairies. Locals are asked where the Fairy Glen is, even though the site along the small river is off limits, due to the danger of erosion.

The story begins with Elsie borrowing her father’s camera one Saturday afternoon in July 1917, in order to take Frances’s photo, to cheer her up. She had fallen in the beck and been scolded for wetting her clothes. The girls were away for about half an hour and when Elsie’s father developed the plate later in the afternoon, he was surprised to see strange white shapes coming up. He believed these were birds, then sandwich paper, but it was Elsie who told him these were fairies. Apparently, in order to prove that fairies really did exist, Elsie had taken the picture, showing Frances with a troop of sprites dancing in front of her.

In August, the roles were reversed and Frances took a photograph of Elsie with a gnome. The print was under-exposed and unclear, as might be expected when taken by a ten year old. The plate was again developed by Elsie’s father, who suspected that the girls had been playing tricks and refused to lend his camera to them any more. Elsie’s parents searched the girls’ bedroom and waste-paper basket for any scraps of pictures or cut-outs, and also went down to the beck to search for evidence of fakery. They found nothing, and the girls stuck to their story: they had seen fairies and photographed them.

The event was spoken of between friends and family, but that was all. Frances Griffiths sent a letter to a friend in South Africa, where she had lived most of her life. Dated November 9, 1918, she included a photograph of the fairies, and wrote: “I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, Uncle Arthur took that, while the other is me with some fairies up the beck, Elsie took that one.” The letter continued, matter of factly: “Rosebud is as fat as ever and I have made her some new clothes. How are Teddy and dolly?” On the back of photograph, it read: “Elsie and I are very friendly with the beck Fairies. It is funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there.”

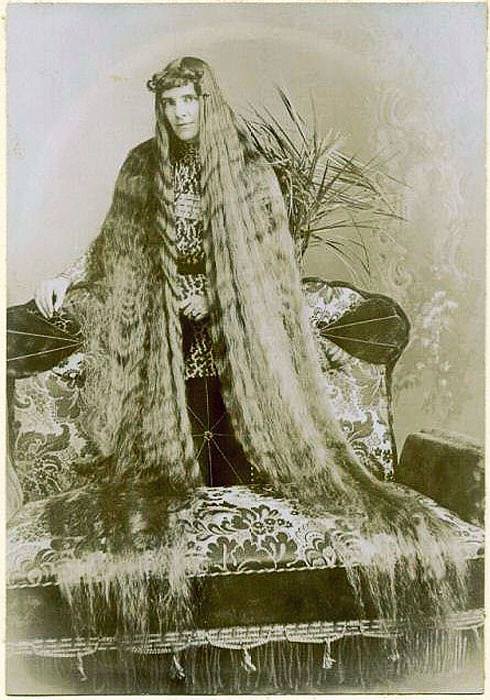

The case’s first publicity occurred in the summer of 1919, when Polly Wright, Elsie’s mother, went to a meeting of the Theosophical Society in nearby Bradford. She was interested in the occult, having had some experiences of astral projection and memories of past lives. Theosophy, founded by Helena Blavatsky, was the main engine that drove this interest across Britain.

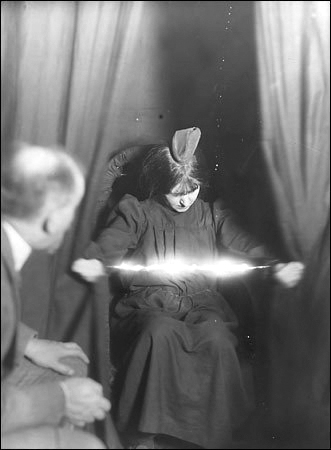

The lecture was on fairy life and Polly mentioned that her daughter and a niece had taken some photographs of fairy. It would be sensational evidence, if only because another dimensional entity had been able to be caught on camera; it is on par with the photographic evidence of a UFOs or alien beings. But whereas the latter have seldom if ever lived up to the stringent methods that would constitute scientific proof, two girls, decades earlier, had apparently succeeded where most adults failed.

The two rough prints moved their way through Theosophical circles and came to the notice of Theosophists at a Harrogate conference in the autumn, and eventually arrived with a leading Theosophist, Edward Gardner, by early 1920.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes, as well as a Freemason and a Spiritualist, had been commissioned by the Strand Magazine to write an article on fairies for their Christmas 1920 issue. He was preparing this in June, when he heard of the two fairy prints. He contacted Gardner and borrowed the copies. Still, contrary to what is often reported, Conan Doyle was on his guard. He showed the prints to Sir Oliver Lodge, a pioneer psychical researcher, who thought them fakes, perhaps involving a troupe of dancers masquerading as fairies. One fairy authority told him that the hairstyles of the sprites were too ‘Parisienne’ for his liking. Intriguingly, no-one apparently wanted to examine the original photographs; only the prints were analysed and the two prints, in an enhanced version, would appear in the magazine.

Conan Doyle sent Gardner to Cottingley in July. He reported that the whole Wright family seemed honest and totally respectable. In August, he returned with cameras and 20 photographic plates, leaving them with Elsie and Frances, hoping to persuade them to take more photographs. Meanwhile, the Strand article was completed, featuring the two sharpened prints, and Conan Doyle sailed for Australia and a lecture tour.

The issue of the Strand sold out within days of publication and it was largely due to the photographic evidence that fairies existed. It caused major controversy and reactions from all involved – and those feeling they had to comment. Most were sceptical, including Major Hall-Edwards, a radium expert. He declared: “On the evidence I have no hesitation in saying that these photographs could have been ‘faked’.”

With the plates left by Gardner, Elsie and Frances took three more fairy photographs. The fifth picture in the entire series, the Fairy Sunbath, was created with a simple frame and knicker elastic construction pushed into the long grass. With a pull of the elastic, the fairies would fall backwards from their slots in the frame, thus providing a sense of “fading” when the camera caught the motion; they were “dancing”.

Her father returned the plates to London, wrapped in cotton wool. Arthur Wright was greatly puzzled. He understood the photographs were faked, irrespective of him and his wife not finding incriminating evidence that showed their daughter had done it. Still, he could not understand that other grown men had been fooled. Furthermore, his daughter was now the centre of a nationwide, if not international, sensation. As Conan Doyle had used pseudonyms, the children were fairly safe from public scrutiny, but Arthur Wright began to have a lower estimation of Conan Doyle. He found it hard to believe that such an intelligent man could be bamboozled “by our Elsie, and her at the bottom of the class!” Riding on the controversy, a last expedition was made to Cottingley in August 1921. The clairvoyant Geoffrey Hodson had been asked to verify any fairy sightings. The fairies refused to be photographed, though both by Hodson and Elsie stated they had seen them. Elsie and Frances later admitted they had deceived him, pointing out faeries were none were seen by them. The “clairvoyant” nevertheless saw them; or perhaps he felt he had to substantiate Elsie claim; could he deny seeing anything? With the knowledge that the photographs were hoaxed, it is intriguing to analyze how the controversy originated. The children’s parents were largely sceptical, though Polly seems to have used the photographs to promote the belief in faeries. Conan Doyle may have done the same, or may merely have used them to boost his article and the sales of the magazine. In general, there was a willingness to believe: how could children fool their parents?

The children themselves – truthfully or not – stated they had seen faeries in the beck. Even if they are lying, there is a multitude of people who believe in faeries and have “seen” them. The girls differed in the fact that they had been able to photograph them. The belief in faeries was there – it was widespread and those who believed, but had no evidence, used the photographs to substantiate their own beliefs and try to convince the more sceptical of mind of the validity of the fairy realm. We all know what sprinkling fairy dust means, and it seems that it was fervently thrown about…

There were many who did not believe in faeries. They pointed out that no third party was ever present when the five photographs were taken. They pointed out – correctly – that Elsie painted and drew well, that she had always seemed immersed in drawing fairies, that she was quite knowledgeable about photography and had worked at a photographer’s. The latter only made her quite an able photographer, though some asked whether the photographs – the plates – had been tampered with. We now know this was not the case; “animated drawings” were used instead.

In general, the sceptics were unable to prove the photographs were faked. As late as 1978, James Randi and a team from New Scientists studied the photographs and thought they could see strings attached to some figures. There were none… hatpins were used. But the believers did not fare better. The point of a pin in the gnome’s midriff was, according to Conan Doyle, an umbilicus and therefore proof that birth in the fairy kingdom might be a similar process to human birth. The gnome photograph was taken by Frances, a less expert photographer than Elsie. The elongated hand in the picture is due to camera slant, though believers have attributed it to “psychic elongation”. In 1981 and 1982, Joe Cooper interviewed Frances and Elsie for an article in The Unexplained. Elsie admitted that all five of the photographs had been faked. Frances had a copy of Princess Mary’s Gift Book and the girls had used a series of illustrations by Arthur Shepperson as a model from which Elsie constructed the fairy figures. Frances also admitted the hoax, claimed that the first four photographs had been faked, but the fifth was real. Both ladies contended they had indeed seen real fairies near the beck.

The admission was not totally out of the blue. In 1971, Elsie, interviewed for BBC TV, was asked: “Are they trick photographs? Could you swear on the Bible about that?” Elsie (after a pause): “I’d rather leave that open if you don’t mind… but my father had nothing to do with it I can promise you that…”

The attitude of Elsie and Frances to the whole question of the fairy photographs had been a typical Yorkshire one: to tell a tall story with a deadpan delivery and let those who will believe it do so. Indeed, Elsie has often said as much: “I would rather we were thought of as solemn faced comediennes.” But the carrot they dangled was just so nice that many decided to eat it…

In 1983, when Geoffrey Hodson was 96 and living in New Zealand, he heard the true confessions and thus became the only surviving member of Gardner’s team to know the truth. As to the man who had made them famous: Conan Doyle published “The Coming of the Fairies” in 1922. The book was not solely based on events in Cottingley but was a collection of fairy stories and sightings all over the world. On July 8, 1930, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died, apparently still believing in fairies. In 1966, almost 50 years after the story was hatched, Gardner released “Pictures of Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs”, which would begin a series of accounts which would take almost a further 20 years before the then grandparents admitted the hoax.

The Cottlingley fairies are primary evidence that it does not take faeries to sprinkle fairy dust; humans are perfectly able to do that themselves.

The event was spoken of between friends and family, but that was all. Frances Griffiths sent a letter to a friend in South Africa, where she had lived most of her life. Dated November 9, 1918, she included a photograph of the fairies, and wrote: “I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, Uncle Arthur took that, while the other is me with some fairies up the beck, Elsie took that one.” The letter continued, matter of factly: “Rosebud is as fat as ever and I have made her some new clothes. How are Teddy and dolly?” On the back of photograph, it read: “Elsie and I are very friendly with the beck Fairies. It is funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there.”

The event was spoken of between friends and family, but that was all. Frances Griffiths sent a letter to a friend in South Africa, where she had lived most of her life. Dated November 9, 1918, she included a photograph of the fairies, and wrote: “I am sending two photos, both of me, one of me in a bathing costume in our back yard, Uncle Arthur took that, while the other is me with some fairies up the beck, Elsie took that one.” The letter continued, matter of factly: “Rosebud is as fat as ever and I have made her some new clothes. How are Teddy and dolly?” On the back of photograph, it read: “Elsie and I are very friendly with the beck Fairies. It is funny I never used to see them in Africa. It must be too hot for them there.” The issue of the Strand sold out within days of publication and it was largely due to the photographic evidence that fairies existed. It caused major controversy and reactions from all involved – and those feeling they had to comment. Most were sceptical, including Major Hall-Edwards, a radium expert. He declared: “On the evidence I have no hesitation in saying that these photographs could have been ‘faked’.”

The issue of the Strand sold out within days of publication and it was largely due to the photographic evidence that fairies existed. It caused major controversy and reactions from all involved – and those feeling they had to comment. Most were sceptical, including Major Hall-Edwards, a radium expert. He declared: “On the evidence I have no hesitation in saying that these photographs could have been ‘faked’.” There were many who did not believe in faeries. They pointed out that no third party was ever present when the five photographs were taken. They pointed out – correctly – that Elsie painted and drew well, that she had always seemed immersed in drawing fairies, that she was quite knowledgeable about photography and had worked at a photographer’s. The latter only made her quite an able photographer, though some asked whether the photographs – the plates – had been tampered with. We now know this was not the case; “animated drawings” were used instead.

There were many who did not believe in faeries. They pointed out that no third party was ever present when the five photographs were taken. They pointed out – correctly – that Elsie painted and drew well, that she had always seemed immersed in drawing fairies, that she was quite knowledgeable about photography and had worked at a photographer’s. The latter only made her quite an able photographer, though some asked whether the photographs – the plates – had been tampered with. We now know this was not the case; “animated drawings” were used instead. In 1983, when Geoffrey Hodson was 96 and living in New Zealand, he heard the true confessions and thus became the only surviving member of Gardner’s team to know the truth. As to the man who had made them famous: Conan Doyle published “The Coming of the Fairies” in 1922. The book was not solely based on events in Cottingley but was a collection of fairy stories and sightings all over the world. On July 8, 1930, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died, apparently still believing in fairies. In 1966, almost 50 years after the story was hatched, Gardner released “Pictures of Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs”, which would begin a series of accounts which would take almost a further 20 years before the then grandparents admitted the hoax.

In 1983, when Geoffrey Hodson was 96 and living in New Zealand, he heard the true confessions and thus became the only surviving member of Gardner’s team to know the truth. As to the man who had made them famous: Conan Doyle published “The Coming of the Fairies” in 1922. The book was not solely based on events in Cottingley but was a collection of fairy stories and sightings all over the world. On July 8, 1930, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle died, apparently still believing in fairies. In 1966, almost 50 years after the story was hatched, Gardner released “Pictures of Fairies: The Cottingley Photographs”, which would begin a series of accounts which would take almost a further 20 years before the then grandparents admitted the hoax.