Hello. I'm writer Antoinette Beard... WOO-HOO-HOO!!! This is sensual, bizarre & macabre. Keep scrolling after the posts for much weird info and wonky photos. Also, use the "Search Box" to discover more quirky fascinations. Outwardly, Victorians were conformists, but there are always those who delight in flaunting conventions. ADULT CONTENT, --- naturally. ;)

Friday, March 31, 2017

Wednesday, March 29, 2017

Tuesday, March 28, 2017

William Butler Yeats, - Poet, Noble Prize Winner, Believer In Faeries & Spiritualist...

William Butler Yeats photographed in 1903 by Alice Boughton

William Butler Yeats (/ˈjeɪts/; 13 June 1865 – 28 January 1939) was an Irish poet and one of the foremost figures of 20th-century literature. A pillar of both the Irish and British literary establishments, he helped to found the Abbey Theatre, and in his later years served as an Irish Senator for two terms. Yeats was a driving force behind the Irish Literary Revival along with Lady Gregory, Edward Martyn and others.

He was born in Sandymount, Ireland and educated there and in London. He spent childhood holidays in County Sligo and studied poetry from an early age when he became fascinated by Irish legends and the occult. These topics feature in the first phase of his work, which lasted roughly until the turn of the 20th century. His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced and lyrical poems display Yeats's debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. From 1900, his poetry grew more physical and realistic. He largely renounced the transcendental beliefs of his youth, though he remained preoccupied with physical and spiritual masks, as well as with cyclical theories of life. In 1923, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Biography

Early years

Of Anglo-Irish descent,[1] William Butler Yeats was born at Sandymount in County Dublin, Ireland.[2] His father, John Butler Yeats (1839–1922), was a descendant of Jervis Yeats, a Williamite soldier, linen merchant, and well-known painter who died in 1712.[3] Benjamin Yeats, Jervis's grandson and William's great-great-grandfather, had in 1773[4] married Mary Butler[5] of a landed family in County Kildare.[6] Following their marriage, they kept the name Butler in the family name. Mary was a descendant of the Butler of Ormond family from the Neigham (pronounced Nyam) Gowran branch of the family. They were descendants of the first Earls of Ormond.

By his marriage, William's father John Yeats was studying law but abandoned his studies to study art at Heatherley's Art School in London.[7] His mother, Susan Mary Pollexfen, came from a wealthy merchant family in Sligo, who owned a milling and shipping business. Soon after William's birth the family relocated to the Pollexfen home at Merville, Sligo to stay with her extended family, and the young poet came to think of the area as his childhood and spiritual home. Its landscape became, over time, both literally and symbolically, his "country of the heart"[8] So also did its location on the sea; John Yeats stated that "by marriage with a Pollexfen, we have given a tongue to the sea cliffs".[9] The Butler Yeats family were highly artistic; his brother Jack became an esteemed painter, while his sisters Elizabeth and Susan Mary—known to family and friends as Lollie and Lily—became involved in the Arts and Crafts movement.[10]

Yeats was raised a member of the Protestant Ascendancy, which was at the time undergoing a crisis of identity. While his family was broadly supportive of the changes Ireland was experiencing, the nationalist revival of the late 19th century directly disadvantaged his heritage, and informed his outlook for the remainder of his life. In 1997, his biographer R. F. Foster observed that Napoleon's dictum that to understand the man you have to know what was happening in the world when he was twenty "is manifestly true of W.B.Y."[11]Yeats's childhood and young adulthood were shadowed by the power-shift away from the minority Protestant Ascendancy. The 1880s saw the rise of Charles Stewart Parnell and the home rule movement; the 1890s saw the momentum of nationalism, while the Catholics became prominent around the turn of the century. These developments had a profound effect on his poetry, and his subsequent explorations of Irish identity had a significant influence on the creation of his country's biography.[12]

In 1867, the family moved to England to aid their father, John, to further his career as an artist. At first the Yeats children were educated at home. Their mother entertained them with stories and Irish folktales. John provided an erratic education in geography and chemistry, and took William on natural history explorations of the nearby Slough countryside.[13] On 26 January 1877, the young poet entered the Godolphin school,[14] which he attended for four years. He did not distinguish himself academically, and an early school report describes his performance as "only fair. Perhaps better in Latin than in any other subject. Very poor in spelling".[15] Though he had difficulty with mathematics and languages (possibly because he was tone deaf[16]), he was fascinated by biology and zoology. For financial reasons, the family returned to Dublin toward the end of 1880, living at first in the suburbs of Harold's Cross[17] and later Howth. In October 1881, Yeats resumed his education at Dublin's Erasmus Smith High School.[18] His father's studio was nearby and William spent a great deal of time there, where he met many of the city's artists and writers. During this period he started writing poetry, and, in 1885, the Dublin University Review published Yeats's first poems, as well as an essay entitled "The Poetry of Sir Samuel Ferguson". Between 1884 and 1886, William attended the Metropolitan School of Art—now the National College of Art and Design—in Thomas Street.[2]

He began writing his first works when he was seventeen; these included a poem—heavily influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley—that describes a magician who set up a throne in central Asia. Other pieces from this period include a draft of a play about a bishop, a monk, and a woman accused of paganism by local shepherds, as well as love-poems and narrative lyrics on German knights. The early works were both conventional and, according to the critic Charles Johnston, "utterly unIrish", seeming to come out of a "vast murmurous gloom of dreams".[19] Although Yeats's early works drew heavily on Shelley, Edmund Spenser, and on the diction and colouring of pre-Raphaelite verse, he soon turned to Irish mythology and folklore and the writings of William Blake. In later life, Yeats paid tribute to Blake by describing him as one of the "great artificers of God who uttered great truths to a little clan".[20] In 1891, Yeats published John Sherman and "Dhoya", one a novella, the other a story.

Young poet

1900 portrait by John Butler Yeats

The family returned to London in 1887. In March 1890 Yeats joined the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, and with Ernest Rhys[21] co-founded the Rhymers' Club, a group of London-based poets who met regularly in a Fleet Street tavern to recite their verse. Yeats later sought to mythologize the collective, calling it the "Tragic Generation" in his autobiography,[22] and published two anthologies of the Rhymers' work, the first one in 1892 and the second one in 1894. He collaborated with Edwin Ellis on the first complete edition of William Blake's works, in the process rediscovering a forgotten poem, "Vala, or, the Four Zoas".[23][24]

Yeats had a life-long interest in mysticism, spiritualism, occultism and astrology. He read extensively on the subjects throughout his life, became a member of the paranormal research organisation "The Ghost Club" (in 1911) and was especially influenced by the writings of Emanuel Swedenborg.[25] As early as 1892, he wrote: "If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book, nor would The Countess Kathleen ever have come to exist. The mystical life is the centre of all that I do and all that I think and all that I write."[26]His mystical interests—also inspired by a study of Hinduism, under the Theosophist Mohini Chatterjee, and the occult—formed much of the basis of his late poetry. Some critics disparaged this aspect of Yeats's work; W. H. Auden called it the "deplorable spectacle of a grown man occupied with the mumbo-jumbo of magic and the nonsense of India."[27]

His first significant poem was "The Island of Statues", a fantasy work that took Edmund Spenser and Shelley for its poetic models. The piece was serialized in the Dublin University Review. Yeats wished to include it in his first collection, but it was deemed too long, and in fact was never republished in his lifetime. Quinx Books published the poem in complete form for the first time in 2014. His first solo publication was the pamphlet Mosada: A Dramatic Poem (1886), which comprised a print run of 100 copies paid for by his father. This was followed by the collection The Wanderings of Oisin and Other Poems (1889), which arranged a series of verse that dated as far back as the mid-1880s. The long title poem contains, in the words of his biographer R.F. Foster, "obscure Gaelic names, striking repetitions [and] an unremitting rhythm subtly varied as the poem proceeded through its three sections";[28]

We rode in sorrow, with strong hounds three,

Bran, Sceolan, and Lomair,

On a morning misty and mild and fair.

The mist-drops hung on the fragrant trees,

And in the blossoms hung the bees.

We rode in sadness above Lough Lean,

For our best were dead on Gavra's green.

Bran, Sceolan, and Lomair,

On a morning misty and mild and fair.

The mist-drops hung on the fragrant trees,

And in the blossoms hung the bees.

We rode in sadness above Lough Lean,

For our best were dead on Gavra's green.

"The Wanderings of Oisin" is based on the lyrics of the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and displays the influence of both Sir Samuel Ferguson and the Pre-Raphaelite poets.[29]The poem took two years to complete and was one of the few works from this period that he did not disown in his maturity. Oisin introduces what was to become one of his most important themes: the appeal of the life of contemplation over the appeal of the life of action. Following the work, Yeats never again attempted another long poem. His other early poems, which are meditations on the themes of love or mystical and esoteric subjects, include Poems (1895), The Secret Rose (1897), and The Wind Among the Reeds (1899). The covers of these volumes were illustrated by Yeats's friend Althea Gyles.[30]

During 1885, Yeats was involved in the formation of the Dublin Hermetic Order. The society held its first meeting on 16 June, with Yeats acting as its chairman. The same year, the Dublin Theosophical lodge was opened in conjunction with Brahmin Mohini Chatterjee, who travelled from the Theosophical Society in London to lecture. Yeats attended his first séance the following year. He later became heavily involved with the Theosophical Society and with hermeticism, particularly with the eclectic Rosicrucianism of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. During séances held from 1912, a spirit calling itself "Leo Africanus" apparently claimed it was Yeats's Daemon or anti-self, inspiring some of the speculations in Per Amica Silentia Lunae.[31] He was admitted into the Golden Dawn in March 1890 and took the magical motto Daemon est Deus inversus—translated as Devil is God inverted or A demon is a god reflected.[32] He was an active recruiter for the sect's Isis-Urania Temple, and brought in his uncle George Pollexfen, Maud Gonne, and Florence Farr. Although he reserved a distaste for abstract and dogmatic religions founded around personality cults, he was attracted to the type of people he met at the Golden Dawn.[33] He was involved in the Order's power struggles, both with Farr and Macgregor Mathers, and was involved when Mathers sent Aleister Crowley to repossess Golden Dawn paraphernalia during the "Battle of Blythe Road". After the Golden Dawn ceased and splintered into various offshoots, Yeats remained with the Stella Matutina until 1921.[34]

Maud Gonne

Maud Gonne c. 1900

In 1889, Yeats met Maud Gonne, a 23-year-old English heiress and ardent Irish Nationalist.[35] She was eighteen months younger than Yeats and later claimed she met the poet as a "paint-stained art student."[36] Gonne admired "The Island of Statues" and sought out his acquaintance. Yeats began an obsessive infatuation, and she had a significant and lasting effect on his poetry and his life thereafter.[37] In later years he admitted, "it seems to me that she [Gonne] brought into my life those days—for as yet I saw only what lay upon the surface—the middle of the tint, a sound as of a Burmese gong, an over-powering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes."[38] Yeats's love was unrequited, in part due to his reluctance to participate in her nationalist activism.[39]

In 1891 he visited Gonne in Ireland and proposed marriage, but was rejected. He later admitted that from that point "the troubling of my life began".[40] Yeats proposed to Gonne three more times: in 1899, 1900 and 1901. She refused each proposal, and in 1903, to his horror, married the Irish nationalist Major John MacBride.[41] His only other love affair during this period was with Olivia Shakespear, whom he first met in 1894, and parted from in 1897.

Yeats derided MacBride in letters and in poetry. He was horrified by Gonne's marriage, at losing his muse to another man; in addition her conversion to Catholicism before marriage offended him, although he was Protestant/agnostic. He worried his muse would come under the influence of the priests and do their bidding.[42]

Gonne's marriage to MacBride was a disaster. This pleased Yeats, as Gonne began to visit him in London. After the birth of her son, Seán MacBride, in 1904, Gonne and MacBride agreed to end the marriage, although they were unable to agree on the child's welfare. Despite the use of intermediaries, a divorce case ensued in Paris in 1905. Gonne made a series of allegations against her husband with Yeats as her main 'second', though he did not attend court or travel to France. A divorce was not granted, for the only accusation that held up in court was that MacBride had been drunk once during the marriage. A separation was granted, with Gonne having custody of the baby and MacBride having visiting rights.[43]

Yeats's friendship with Gonne ended, yet, in Paris in 1908, they finally consummated their relationship. "The long years of fidelity rewarded at last" was how another of his lovers described the event. Yeats was less sentimental and later remarked that "the tragedy of sexual intercourse is the perpetual virginity of the soul."[40] The relationship did not develop into a new phase after their night together, and soon afterwards Gonne wrote to the poet indicating that despite the physical consummation, they could not continue as they had been: "I have prayed so hard to have all earthly desire taken from my love for you and dearest, loving you as I do, I have prayed and I am praying still that the bodily desire for me may be taken from you too."[44] By January 1909, Gonne was sending Yeats letters praising the advantage given to artists who abstain from sex. Nearly twenty years later, Yeats recalled the night with Gonne in his poem "A Man Young and Old":[45]

My arms are like the twisted thorn

And yet there beauty lay;

The first of all the tribe lay there

And did such pleasure take;

She who had brought great Hector down

And put all Troy to wreck.

And yet there beauty lay;

The first of all the tribe lay there

And did such pleasure take;

She who had brought great Hector down

And put all Troy to wreck.

In 1896, Yeats was introduced to Lady Gregory by their mutual friend Edward Martyn. Gregory encouraged Yeats's nationalism, and convinced him to continue focusing on writing drama. Although he was influenced by French Symbolism, Yeats concentrated on an identifiably Irish content and this inclination was reinforced by his involvement with a new generation of younger and emerging Irish authors. Together with Lady Gregory, Martyn, and other writers including J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey, and Padraic Colum, Yeats was one of those responsible for the establishment of the "Irish Literary Revival" movement.[46] Apart from these creative writers, much of the impetus for the Revival came from the work of scholarly translators who were aiding in the discovery of both the ancient sagas and Ossianic poetry and the more recent folk song tradition in Irish. One of the most significant of these was Douglas Hyde, later the first President of Ireland, whose Love Songs of Connacht was widely admired.

Monday, March 27, 2017

Who Was Irene Adler In The Sherlock Holmes Novels, - And Was She Based On A Real Person???...

| Irene Adler | |

|---|---|

| Sherlock Holmes character | |

| First appearance | "A Scandal in Bohemia" |

| Created by | Sir Arthur Conan Doyle |

| Information | |

| Gender | Female |

| Occupation | Opera singer |

| Spouse(s) | Godfrey Norton |

| Nationality | American |

Irene Adler is a fictional character in the Sherlock Holmes stories written by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. She was featured in the short story "A Scandal in Bohemia", published in July 1891. She is one of the most notable female characters in the Sherlock Holmes series, despite appearing in only one story,[1] and is frequently used as a romantic interest for Holmes in derivative works.

Fictional character biography]

According to "A Scandal in Bohemia", Adler was born in New Jersey in 1858. She followed a career in opera as a contralto, performing at La Scala in Milan, Italy, and a term as prima donna in the Imperial Opera of Warsaw, Poland, indicating that she was a talented singer. It was there that she became the lover of Wilhelm Gottsreich Sigismond von Ormstein, Grand Duke of Cassel-Felstein and King of Bohemia, who was staying in Warsaw for a period. The King describes her as "a well-known adventuress" (a term widely used at the time in ambiguous association with "courtesan"[2][3]) and also says that she had "the face of the most beautiful of women and the mind of the most resolute of men". The King eventually returned to his court in Prague. Adler, then in her late twenties, retired from the opera stage and moved to London.

On 20 March 1888, the King makes an incognito visit to Holmes in London. He asks the famous detective to secure possession of a previously taken photograph depicting Adler and the King together. The 30-year-old King explains to Holmes that he intends to marry Clotilde Lothman von Saxe-Meiningen, second daughter of the King of Scandinavia; the marriage would be threatened if his prior relationship with Adler were to come to light. He also reveals he had hired burglars to attempt to retrieve it twice, had Adler herself waylaid, and her luggage stolen, to no avail.

A disguised Holmes traces her movements, learning of her private life and, notably, stands witness to her marriage to Godfrey Norton, an English lawyer. Holmes disguises himself as an elderly cleric and sets up a faked incident to cause a diversion that is designed to gain him access to Adler's home and to trick her into revealing where the picture is hidden. Adler treats him kindly as the supposed victim of a crime outside her home. At the moment she gives away the location of the photograph, she realises she has been tricked. She tests her theory that it is indeed Holmes, of whom she had been warned, by disguising herself as a young man and wishing him good night as he and Watson return to 221B Baker Street.

Holmes visits Adler's home the next morning with Watson and the King to demand the return of the photograph. He finds Adler gone, along with her new husband and the original photo, which has been replaced with a photograph of her alone as well as a letter to Holmes. The letter explains how she had outwitted him, but also that she is happy with her new husband, who has more honourable feelings than her former lover. Adler adds that she will not compromise the King and has kept the photo only to protect herself against any further action the King might take. In the face of this and the King's statement that it was a "pity that she was not on my level", Holmes then decides that Adler was the wronged party rather than the King and asks, when offered a reward by the King, only for the photograph that Adler had left.

In the opening paragraph of the short story, Watson calls her "the late Irene Adler", suggesting her death sometime between early 1888 (the story's setting) and mid 1891 (the publication of "A Scandal in Bohemia").

Character sources

Adler's career as a theatrical performer who becomes the lover of a powerful aristocrat had several precedents. One is Lola Montez, a dancer who became the lover of Ludwig I of Bavaria and influenced national politics. Montez is suggested as a model for Adler by several writers.[4]

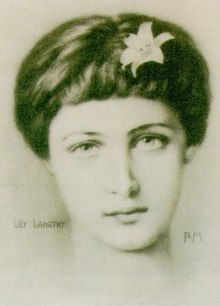

Another possibility is the singer Lillie Langtry, the lover of Edward, the Prince of Wales.[4] Julian Wolff[who?] points out, it was well known that Langtry was born in Jersey (she was called the "Jersey Lily") and Adler is born in New Jersey.[3] Langtry had later had several other aristocratic lovers, and her relationships had been speculated upon in the public press in the years before Doyle's story was published. Another suggestion is the singer Ludmilla Stubel, the alleged lover and later wife of Archduke Johann Salvator of Austria.[5]

Appearances

Irene Adler appears only in "A Scandal in Bohemia". Her name is briefly mentioned in "A Case of Identity", "The Adventure of the Blue Carbuncle" and "His Last Bow". Additionally, in "The Five Orange Pips."

Holmes' relationship to Adler

Adler earns Holmes' unbounded admiration. When the King of Bohemia says, "Would she not have made an admirable queen? Is it not a pity she was not on my level?" Holmes replies scathingly that Adler is indeed on a much different level from the King.

The beginning of "A Scandal in Bohemia" describes the high regard in which Holmes held Adler:

To Sherlock Holmes she is always the woman. I have seldom heard him mention her under any other name. In his eyes she eclipses and predominates the whole of her sex. It was not that he felt any emotion akin to love for Irene Adler. All emotions, and that one particularly, were abhorrent to his cold, precise but admirably balanced mind. He was, I take it, the most perfect reasoning and observing machine that the world has seen, but as a lover he would have placed himself in a false position. He never spoke of the softer passions, save with a gibe and a sneer. They were admirable things for the observer—excellent for drawing the veil from men's motives and actions. But for the trained reasoner to admit such intrusions into his own delicate and finely adjusted temperament was to introduce a distracting factor which might throw a doubt upon all his mental results. Grit in a sensitive instrument, or a crack in one of his own high-power lenses, would not be more disturbing than a strong emotion in a nature such as his. And yet there was but one woman to him, and that woman was the late Irene Adler, of dubious and questionable memory.

This "memory" is kept alive by a photograph of Irene Adler, which had been deliberately left behind when she and her new husband took flight with the embarrassing photograph of her with the King. Holmes had then asked for and received this photo from the King, as payment for his work on the case.

Books

In his fictional biographies of Sherlock Holmes and Nero Wolfe, William S. Baring-Gould puts forth an argument that Adler and Holmes meet again after the latter's supposed death at Reichenbach Falls. They perform on stage together incognito, and become lovers. According to Baring-Gould, Holmes and Adler's union produces one son, Nero Wolfe, who would follow in his father's footsteps as a detective.

Irene Adler appears as an opera singer in The Canary Trainer, where she encounters Holmes during his three-year 'death' while he is working as a violinist in the Paris Opera House, and asks him to help her protect her friend and unofficial protege, Christine Daaé, from the 'Opera Ghost'.

A series of mystery novels written by Carole Nelson Douglas features Irene Adler as the protagonist and sleuth, chronicling her life shortly before (in the novel Good Night, Mr. Holmes) and after her notable encounter with Sherlock Holmes and which feature Holmes as a supporting character. The series includes Godfrey Norton as Irene's supportive barrister husband; Penelope "Nell" Huxleigh, a vicar's daughter and former governess who is Irene's best friend and biographer; and Nell's love interest Quentin Stanhope. Historical characters such as Oscar Wilde, Bram Stoker, Alva Vanderbilt and Consuelo Vanderbilt, and journalist Nellie Bly, among others, also make appearances. In the books, Douglas strongly implies that Irene's mother was Lola Montez and her father possibly Ludwig I of Bavaria. Douglas provides Irene with a back story as a pint-size child vaudeville performer who was trained as an opera singer before going to work as a Pinkerton detective.

In a series of novels by John Lescroart, it is stated that Adler and Holmes had a son, Auguste Lupa, and it is implied that he later changes his name to Nero Wolfe.

In the 2009 novel The Language of Bees by Laurie R. King, it is stated that Irene Adler, who is deceased when the book begins, once had an affair with main character Sherlock Holmes and gave birth to a son, Damian Adler, an artist now known as The Addler.

In a recent collection of Sherlock Holmes pastiches entitled Sherlock Holmes: The Golden Years, the story "A Bonnie Bag of Bones", and several stories that follow, reveal that "the woman" is reunited with Sherlock Holmes. This series of tales provides great insights into the relationship of Adler and Holmes.

Films

In the 1946 film Dressed to Kill, Adler is mentioned early in the film when Holmes and Watson discuss the events of "A Scandal in Bohemia".

In the 1976 film Sherlock Holmes in New York, Adler (Charlotte Rampling) helps Holmes and Watson to solve a bank robbery organised by Holmes' nemesis, Professor Moriarty, after he takes her son hostage to prevent Holmes from investigating the case. Holmes and Watson later rescue the boy, with a final conversation between Holmes and Adler at the conclusion of the case implying that Holmes may be the boy's father.

She is portrayed by Rachel McAdams in the 2009 film Sherlock Holmes. In that film, she is a skilled professional thief, as well as a divorcée. In the film, Adler is no longer married to Godfrey Norton and needs Holmes' help for the case.[6]It is known that she knew Holmes prior to the events of the film. In this aspect the film considerably departs from Doyle's original, where Holmes never met Adler again after the one occasion where she outwitted (and greatly impressed) him; the film conversely implies that the two of them met many times and later had an intermittent, hotly consummated love affair. She and Holmes are depicted as having a deep and mutual infatuation, even while she is employed by Moriarty.

McAdams reprised the role in the 2011 sequel Sherlock Holmes: A Game of Shadows in which Professor Moriarty poisons her, apparently killing her — deeming her position compromised by her love for Holmes.

Monday, March 20, 2017

The "From Hell" Letter [1888] May Be The One True Letter From Jack The Ripper...

| Jack the Ripper letters |

|---|

| "Dear Boss" letter |

| "Saucy Jacky" postcard |

| "From Hell" letter |

| Openshaw letter |

The "From Hell" letter (also called the "Lusk letter")[1][2] is a letter that was posted in 1888, along with half a human kidney, by a person who claimed to be the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper. The murderer killed and mutilated at least five female victims in the Whitechapel area of London over a period of several months, the case attracting a great deal of attention both at the time and since. The exact number of victims has never been conclusively proven, and the identity of the perpetrator of the Whitechapel killings has likewise remained unsolved.[2]

Postmarked on 15 October 1888, the letter was received by George Lusk, then head of the Whitechapel Vigilance Committee, the following day. The message was accompanied by a preserved section of a human kidney; the letter's writer claimed to have eaten the other half of the organ. The police received a large number of letters claiming to be from the murderer, at one point having to deal with an estimated one thousand letters related to the case, but the "From Hell" message is one of the few that has received serious attention as possibly being genuine. Opinions on the matter have remained divided.[2]Several fictional works have referred to the Lusk letter, an example being the thriller novel Dust and Shadow.[3]

Letter

The text of the letter reads:[4]

From hell.Mr Lusk,

Sor

I send you half the Kidne I took from one woman and prasarved it for you tother piece I fried and ate it was very nise. I may send you the bloody knif that took it out if you only wate a whil longer

signed

Catch me when you can Mishter Lusk

"Tother" is a grammatically-substandard, regional expression meaning "the other."

The original letter, as well as the kidney that accompanied it, have subsequently been lost along with other items that were originally contained within the Ripper police files. The image shown here is from a photograph taken before the loss.[4]

Background

The news media reacted with alarm at the fact that a multiple murderer was on the loose; the 31 August 1888 death of Mary Ann Nichols resulted in numerous articles about the individual known as "Leather Apron" or "the Whitechapel murderer". The grotesque mutilation of Nichols and later victims were generally described as involving their bodies "ripped up" and residents spoke of their worries of a "ripper" or "high rip" gang. However, the identification of the killer as "Jack" the Ripper did not take place until after 27 September, when the offices of Central News Ltd received the "Dear Boss" letter. The message's writer listed Jack the Ripper as his "trade name" and vowed to continue killing until arrested, also threatening to send the ears of his next victim to the police.[5]

While the newsmen considered the letter a mere joke, they decided after two days to notify Scotland Yard of the matter. The double murder of Elizabeth Stride and Catherine Eddowes took place the night that the police received the "Dear Boss" letter. The Central News people received a second communication known as the "Saucy Jacky" postcard on 1 October 1888, the day after the double murder, and the message was duly passed over to the authorities. Copies of both messages were soon posted to the public in the hopes that the writing style would be recognised. While the police felt determined to discover the author of both messages, they found themselves overwhelmed by the media circus around the Ripper killings and soon received a large amount of material, most of it useless.[5]

Analysis

Though hundreds of letters claiming to be from the killer were posted at the time of the Ripper murders, many researchers argue that the "From Hell" letter is one of a handful of possibly authentic writings received from the murderer.[5] Its author did not sign it with the "Jack the Ripper" pseudonym, distinguishing it from the earlier "Dear Boss" and "Saucy Jacky" messages as well as their many imitators. The handwriting of the earlier two messages mentioned are also similar to each other while being dissimilar to the one made "From Hell".[6] The letter's specific delivery to Lusk personally, without reference made to either the police or the British government generally, could indicate a personal animosity of the writer towards either Lusk as an individual or to the local Whitechapel community establishment (of which Lusk was a member).[7]

The "From Hell" letter is noticeably written at a much lower literacy level than the other two, featuring several errors in spelling and grammar. Scholars have debated whether this is a deliberate misdirection, as the author observed the silent k in 'knif' and h in 'whil'. The formatting of the letter also features a cramped writing style in which letters are pressed together haphazardly; many ink blots appear in a manner that may indicate that the writer was unfamiliar with using a pen.[5] The formatting of the message may point to it being a hoax by an otherwise well-educated individual, but some researchers have argued that it is the genuine work of a partly functional but deranged individual.[6][7]

Opinions of those that have looked into the case are divided. The possibility has been raised that all of the communications supposedly from the Whitechapel murderer are fraudulent, acts done by cranks or by journalists seeking to increase the media frenzy even more. Scotland Yard had reason to doubt the validity of the latter yet ultimately did not take action against suspected reporters.[2][5] However, the many differences between the "From Hell" letter and vast majority of the messages received has been cited by some figures analysing the case, such as a forensic handwriting expert interviewed by the History Channel and another interviewed by the Discovery Channel, as evidence to view it as maybe the only authentic letter.[6][7]

The primary reason this letter stands out more than any other is that it was delivered with a small box containing half of what doctors later determined was a human kidney, preserved in spirits. One of murder victim Catherine Eddowes' kidneys had been removed by the killer. Medical opinion at the time was that the organ could have been acquired by medical students and sent with the letter as part of a hoax.[2][5] Lusk himself believed that this was the case and did not report the letter until he was urged to do so by friends.[8]

Arguments in favour as to the letter's genuineness sometimes state that contemporary analysis of the kidney by Dr. Thomas Openshaw of the London Hospital found that it came from a sickly alcoholic woman who had died within the past three weeks, evidence that it belonged to Eddowes. However, these facts have been in dispute as contemporary media reporting at the time as well as later recollections give contradictory information about Openshaw's opinions. Historian Philip Sugden has written that perhaps all that can be concluded given the uncertainly is that the kidney was human and from the left side of the body.[2][5]

A contemporary police lead found that shopkeeper Emily Marsh had encountered a visitor at her shop, located in London's Mile End Road, with an odd, unsettling manner in both his appearance and speech. The visitor asked Marsh for the address of Mr. Lusk, which he wrote in a personal notebook, before abruptly leaving. He was described as a slim man wearing a long black overcoat at about six feet in height that spoke with an Irish accent, his face featuring a dark beard and mustache. While the event took place the day before Lusk received the "From Hell" message and occurred in the area in which it is considered to have been postmarked, the fact that Lusk received so many hoax letters during this time means that the suspicious individual may have been another crank.[5]

Forensic handwriting expert Michelle Dresbold, working for the History Channel documentary series MysteryQuest, has argued that the letter is genuine based on the peculiar characteristics of the handwriting, particularly the "invasive loop" letter "y"s. The criminal profiling experts in the program also created a profile of the killer, stating that he possessed a deranged animosity towards women and skills at using a knife. Based on linguistic clues (including the use of the particular spelling of the word "prasarved" (preserved), Dresbold felt that the letter showed strong evidence that the writer was Irish or of Irish extraction, linking the letter to Ripper suspect Francis Tumblety. Tumblety was an itinerant Irish-American quack doctor suffering from mentally ill notions of grandiosity who had resided in London during the year of the murders; he had multiple encounters with the law and a strong dislike of women as well as a background collecting body parts. However, after arresting him at the time as a suspect, the police ended up releasing him on bail, having failed to find hard evidence against him. He ultimately died of a heart condition in the U.S. in 1903.[6] Sugden has also written that the author may have had an Irish background but also stated that he may have had Cockney mannerisms.[5]

The purported diary of James Maybrick, another man who has been proposed as a Ripper suspect, contains references to the "From Hell" letter, particularly the alleged cannibalism. However, even if the diary is assumed to be genuine, the handwriting does not match that of the letter at all.[2] A Kirkus Review article has referred to the diary rumor as a "hoax" that is one of several "bizarre hypotheses" relating to the case.[9]

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)