Hello. I'm writer Antoinette Beard... WOO-HOO!!!... Here are quirky fascinations of the Victorian to the Edwardian age, and some things that happened later that were just too bizarre to resist... Such a yummy time of quaintness & blossoming industry. Scroll down for a multitude of coolness... Ha-ha-ha, always there are those who flaunt conventions, Darlings... ;)

Sunday, December 31, 2017

Why Women Fainted So Much in the 19th Century...

Saturday, December 30, 2017

Friday, December 29, 2017

Wednesday, December 27, 2017

Victorian Winter, In London, A Thaw, --- [Reflections on it by Charles Dickens, 1836]...

Victorian London - Weather - Cold weather

A thaw, by all that is miserable! The frost is completely broken up. You look down the long perspective of Oxford-street, the gas-lights mournfully reflected on the wet pavement, and can discern no speck in the road to encourage the belief that there is a cab or a coach to be had - the very coachmen have gone home in despair. The cold sleet is drizzling down with that gentle regularity, which betokens a duration of four-and-twenty hours at least; the damp hangs upon the house-tops and lamp-posts, and clings to you like an invisible cloak. The water is 'coming in' in every area, the pipes have burst, the water-butts are running over; the kennels seem to be doing matches against time, pump-handles descend of their own accord, horses in market-carts fall down, and there's no one to help them up again, policemen look as if they had been carefully sprinkled with powdered glass; here and there a milk-woman trudges slowly along, with a bit of list round each foot to keep her from slipping; boys who 'don't sleep in the house,' and are not allowed much sleep out of it, can't wake their masters by thundering at the shop-door, and cry with the cold - the compound of ice, snow, and water on the pavement, is a couple of inches thick - nobody ventures to walk fast to keep himself warm, and nobody could succeed in keeping himself warm if he did.

Charles Dickens, Sketches by Boz, 1836

Tuesday, December 26, 2017

The Fascinating Life Of Charlotte Bronte, --- Part 3...

In society

In view of the success of her novels, particularly Jane Eyre, Brontë was persuaded by her publisher to make occasional visits to London, where she revealed her true identity and began to move in more exalted social circles, becoming friends with Harriet Martineau and Elizabeth Gaskell, and acquainted with William Makepeace Thackeray and G.H. Lewes. She never left Haworth for more than a few weeks at a time, as she did not want to leave her ageing father. Thackeray’s daughter, writer Anne Isabella Thackeray Ritchie, recalled a visit to her father by Brontë:

... two gentlemen come in, leading a tiny, delicate, serious, little lady, with fair straight hair and steady eyes. She may be a little over thirty; she is dressed in a little barège dress with a pattern of faint green moss. She enters in mittens, in silence, in seriousness; our hearts are beating with wild excitement. This then is the authoress, the unknown power whose books have set all London talking, reading, speculating; some people even say our father wrote the books – the wonderful books. ... The moment is so breathless that dinner comes as a relief to the solemnity of the occasion, and we all smile as my father stoops to offer his arm; for, genius though she may be, Miss Brontë can barely reach his elbow. My own personal impressions are that she is somewhat grave and stern, specially to forward little girls who wish to chatter. ... Everyone waited for the brilliant conversation which never began at all. Miss Brontë retired to the sofa in the study, and murmured a low word now and then to our kind governess ... the conversation grew dimmer and more dim, the ladies sat round still expectant, my father was too much perturbed by the gloom and the silence to be able to cope with it at all ... after Miss Brontë had left, I was surprised to see my father opening the front door with his hat on. He put his fingers to his lips, walked out into the darkness, and shut the door quietly behind him ... long afterwards ... Mrs Procter asked me if I knew what had happened. ... It was one of the dullest evenings [Mrs Procter] had ever spent in her life ... the ladies who had all come expecting so much delightful conversation, and the gloom and the constraint, and how finally, overwhelmed by the situation, my father had quietly left the room, left the house, and gone off to his club.

Brontë's friendship with Elizabeth Gaskell, while not particularly close, was significant in that Gaskell wrote the first biography of Brontë after her death in 1855.

Villette

Brontë's third novel, the last published in her lifetime, was Villette, which appeared in 1853. Its main themes include isolation, how such a condition can be borne, and the internal conflict brought about by social repression of individual desire. It's main character, Lucy Snowe, travels abroad to teach in a boarding school in the fictional town of Villette, where she encounters a culture and religion different from her own, and falls in love with a man (Paul Emanuel) whom she cannot marry. Her experiences result in a breakdown but eventually she achieves independence and fulfilment through running her own school. A substantial amount of the novel's dialogue is in the French language. Villette marked Brontë's return to writing from a first-person perspective (that of Lucy Snowe); the technique she had used in Jane Eyre. Another similarity to Jane Eyre lies in the use of aspects of her own life as inspiration for fictional events;[29] in particular her reworking of the time she spent at the pensionnat in Brussels. Villette was acknowledged by critics of the day as a potent and sophisticated piece of writing although it was criticised for "coarseness" and for not being suitably "feminine" in its portrayal of Lucy's desires.[30]

Marriage

Before the publication of Villette Brontë received a proposal of marriage from Arthur Bell Nicholls, her father's curate, who had long been in love with her. She initially turned down his proposal and her father objected to the union at least partly because of Nicholls's poor financial status. Elizabeth Gaskell, who believed that marriage provided "clear and defined duties" that were beneficial for a woman,[32] encouraged Brontë to consider the positive aspects of such a union and tried to use her contacts to engineer an improvement in Nicholls's finances. Brontë meanwhile was increasingly attracted to Nicholls and by January 1854 she had accepted his proposal. They gained the approval of her father by April and married in June. Her father Patrick had intended to give Charlotte away, but at the last minute decided he could not, and Charlotte had to make her way to the church without him. The married couple took their honeymoon in Banagher, County Offaly, Ireland. By all accounts, her marriage was a success and Brontë found herself very happy in a way that was new to her.

Death[edit]

Brontë became pregnant soon after her wedding, but her health declined rapidly and, according to Gaskell, she was attacked by "sensations of perpetual nausea and ever-recurring faintness". She died, with her unborn child, on 31 March 1855, three weeks before her 39th birthday. Her death certificate gives the cause of death as tuberculosis, but biographers including Claire Harman suggest that she died from dehydration and malnourishment due to vomiting caused by severe morning sickness or hyperemesis gravidarum. There is also evidence that she died from typhus, which she may have caught from Tabitha Ackroyd, the Brontë household's oldest servant, who died shortly before her. Brontë was interred in the family vault in the Church of St Michael and All Angels at Haworth.

The Professor, the first novel Brontë had written, was published posthumously in 1857. The fragment of a new novel she had been writing in her last years has been twice completed by recent authors, the more famous version being Emma Brown: A Novel from the Unfinished Manuscript by Charlotte Brontë by Clare Boylan in 2003. Most of her writings about the imaginary country Angria have also been published since her death.

The Fascinating Life Of Charlotte Bronte, --- Part 2...

Brussels

In 1842 Charlotte and Emily travelled to Brussels to enrol at the boarding school run by Constantin Héger (1809–96) and his wife Claire Zoé Parent Héger (1804–87). During her time in Brussels, Brontë who favoured the Protestant ideal of an individual in direct contact with God, objected to the stern Catholicism of Madame Héger, which she considered to be a tyrannical religion that enforced conformity and submission to the Pope. In return for board and tuition Charlotte taught English and Emily taught music. Their time at the school was cut short when their aunt Elizabeth Branwell, who had joined the family in Haworth to look after the children after their mother's death, died of internal obstruction in October 1842. Charlotte returned alone to Brussels in January 1843 to take up a teaching post at the school. Her second stay was not happy: she was homesick and deeply attached to Constantin Héger. She returned to Haworth in January 1844 and used the time spent in Brussels as the inspiration for some of the events in The Professor and Villette.

First publication

In May 1846 Charlotte, Emily and Anne self-financed the publication of a joint collection of poems under their assumed names Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell. The pseudonyms veiled the sisters' gender while preserving their initials; thus Charlotte was Currer Bell. "Bell" was the middle name of Haworth's curate, Arthur Bell Nicholls whom Charlotte later married, and "Currer" was the surname of Frances Mary Richardson Currer who had funded their school (and maybe their father). Of the decision to use noms de plume, Charlotte wrote:

Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine, while we did not like to declare ourselves women, because — without at that time suspecting that our mode of writing and thinking was not what is called "feminine" – we had a vague impression that authoresses are liable to be looked on with prejudice; we had noticed how critics sometimes use for their chastisement the weapon of personality, and for their reward, a flattery, which is not true praise.

Although only two copies of the collection of poems were sold, the sisters continued writing for publication and began their first novels, continuing to use their noms de plume when sending manuscripts to potential publishers.

The Professor and Jane Eyre

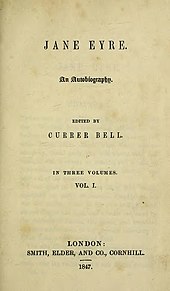

Title page of the first edition of Jane Eyre

Brontë's first manuscript, The Professor, did not secure a publisher, although she was heartened by an encouraging response from Smith, Elder & Co. of Cornhill, who expressed an interest in any longer works Currer Bell might wish to send.[15] Brontë responded by finishing and sending a second manuscript in August 1847. Six weeks later, Jane Eyre was published. It tells the story of a plain governess, Jane, who, after difficulties in her early life, falls in love with her employer, Mr Rochester. They marry, but only after Rochester's insane first wife, of whom Jane initially has no knowledge, dies in a dramatic house fire. The book's style was innovative, combining naturalism with gothic melodrama, and broke new ground in being written from an intensely evoked first-person female perspective.[16] Brontë believed art was most convincing when based on personal experience; in Jane Eyre she transformed the experience into a novel with universal appeal.

Jane Eyre had immediate commercial success and initially received favourable reviews. G. H. Lewes wrote that it was "an utterance from the depths of a struggling, suffering, much-enduring spirit", and declared that it consisted of "suspiria de profundis!" (sighs from the depths). Speculation about the identity and gender of the mysterious Currer Bell heightened with the publication of Wuthering Heights by Ellis Bell (Emily) and Agnes Greyby Acton Bell (Anne). Accompanying the speculation was a change in the critical reaction to Brontë's work, as accusations were made that the writing was "coarse", a judgement more readily made once it was suspected that Currer Bell was a woman. However, sales of Jane Eyrecontinued to be strong and may even have increased as a result of the novel developing a reputation as an "improper" book. A talented amateur artist, Brontë personally did the drawings for the second edition of Jane Eyre and in the summer of 1834 two of her paintings were shown at an exhibition by the Royal Northern Society for the Encouragement of the Fine Arts in Leeds.

Shirley and bereavements

In 1848 Brontë began work on the manuscript of her second novel, Shirley. It was only partially completed when the Brontë family suffered the deaths of three of its members within eight months. In September 1848 Branwell died of chronic bronchitis and marasmus, exacerbated by heavy drinking, although Brontë believed that his death was due to tuberculosis. Branwell was also a suspected "opium eater"; a laudanum addict. Emily became seriously ill shortly after Branwell's funeral and died of pulmonary tuberculosis in December 1848. Anne died of the same disease in May 1849. Brontë was unable to write at this time.

After Anne's death Brontë resumed writing as a way of dealing with her grief, and Shirley, which deals with themes of industrial unrest and the role of women in society, was published in October 1849. Unlike Jane Eyre, which is written in the first person, Shirley is written in the third person and lacks the emotional immediacy of her first novel, and reviewers found it less shocking. Brontë, as her late sister's heir, suppressed the republication of Anne's second novel, The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, an action which had a deleterious effect on Anne's popularity as a novelist and has remained controversial among the sisters' biographers ever since.

The Fascinating Life Of Charlotte Bronte, --- Part 1...

Charlotte Brontë was born on 21 April 1816 in Thornton, west of Bradford in the West Riding of Yorkshire, the third of the six children of Maria (née Branwell) and Patrick Brontë (formerly surnamed Brunty), an Irish Anglican clergyman. In 1820 her family moved a few miles to the village of Haworth, where her father had been appointed perpetual curate of St Michael and All Angels Church. Maria died of cancer on 15 September 1821, leaving five daughters, Maria, Elizabeth, Charlotte, Emily and Anne, and a son, Branwell, to be taken care of by her sister, Elizabeth Branwell.

In August 1824 Patrick sent Charlotte, Emily, Maria and Elizabeth to the Clergy Daughters' School at Cowan Bridge in Lancashire. Charlotte maintained that the school's poor conditions permanently affected her health and physical development, and hastened the deaths of Maria (born 1814) and Elizabeth (born 1815), who both died of tuberculosis in June 1825. After the deaths of his older daughters, Patrick removed Charlotte and Emily from the school. Charlotte used the school as the basis for Lowood School in Jane Eyre.

At home in Haworth Parsonage, Brontë acted as "the motherly friend and guardian of her younger sisters". Brontë wrote her first known poem at the age of 13 in 1829, and was to go on to write more than 200 poems in the course of her life. Many of her poems were "published" in their homemade magazine Branwell's Blackwood's Magazine, and concerned the fictional Glass Town Confederacy. She and her surviving siblings — Branwell, Emily and Anne – created their own fictional worlds, and began chronicling the lives and struggles of the inhabitants of their imaginary kingdoms. Charlotte and Branwell wrote Byronic stories about their jointly imagined country, Angria, and Emily and Anne wrote articles and poems about Gondal. The sagas they created were episodic and elaborate, and they exist in incomplete manuscripts, some of which have been published as juvenilia. They provided them with an obsessive interest during childhood and early adolescence, which prepared them for literary vocations in adulthood.

Between 1831 and 1832, Brontë continued her education at Roe Head in Mirfield, where she met her lifelong friends and correspondents Ellen Nussey and Mary Taylor. In 1833 she wrote a novella, The Green Dwarf, using the name Wellesley. Around about 1833, her stories shifted from tales of the supernatural to more realistic stories. She returned to Roe Head as a teacher from 1835 to 1838. Unhappy and lonely as a teacher at Roe Head, Brontë took out her sorrows in poetry, writing a series of melancholic poems. In "We wove a Web in Childhood" written in December 1835, Brontë drew a sharp contrast between her miserable life as a teacher and the vivid imaginary worlds she and her siblings had created. In another poem "Morning was its freshness still" written at the same time, Brontë wrote "Tis bitter sometimes to recall/Illusions once deemed fair". Many of her poems concerned the imaginary world of Angria, often concerning Byronic heroes, and in December 1836 she wrote to the Poet Laureate Robert Southey asking him for encouragement of her career as a poet. Southey wrote back to say she was a bad poet and to consider another career, a letter that greatly hurt her. One scholar Dawn Potter wrote that Brontë had a streak of sadism in her novels with her characters always suffering in some way, which she suggested was due to her own unhappy life.

In 1839 she took up the first of many positions as governess to families in Yorkshire, a career she pursued until 1841. In particular, from May to July 1839 she was employed by the Sidgwick family at their summer residence, Stone Gappe, in Lothersdale, where one of her charges was John Benson Sidgwick (1835–1927), an unruly child who on one occasion threw a Bible at Charlotte, an incident that may have been the inspiration for a part of the opening chapter of Jane Eyre in which John Reed throws a book at the young Jane. Brontë did not enjoy her work as a governess, noting her employers treated her almost as a slave, constantly humiliating her.

Brontë was of slight build and was less than five feet tall.

"Jane Eyre," By Charlotte Bronte, --- [A masterpiece!!!]...

The novel is a first-person narrative from the perspective of the title character. The novel's setting is somewhere in the north of England, late in the reign of George III (1760–1820).[a]It goes through five distinct stages: Jane's childhood at Gateshead Hall, where she is emotionally and physically abused by her aunt and cousins; her education at Lowood School, where she gains friends and role models but suffers privations and oppression; her time as governess at Thornfield Hall, where she falls in love with her Byronic employer, Edward Rochester; her time with the Rivers family, during which her earnest but cold clergyman cousin, St. John Rivers, proposes to her; and her reunion with, and marriage to, her beloved Rochester. During these sections, the novel provides perspectives on a number of important social issues and ideas, many of which are critical of the status quo. Literary critic Jerome Beaty opines that the close first person perspective leaves the reader "too uncritically accepting of her worldview", and often leads reading and conversation about the novel towards supporting Jane, regardless of how irregular her ideas or perspectives are.

Jane Eyre is divided into 38 chapters, and most editions are at least 400 pages long. The original publication was in three volumes, comprising chapters 1 to 15, 16 to 27, and 28 to 38; this was a common publishing format during the 19th century (see three-volume novel).

Brontë dedicated the novel's second edition to William Makepeace Thackeray.

Jane's childhood...

Young Jane argues with her guardian Mrs. Reed of Gateshead, illustration by F. H. Townsend

The novel begins with the titular character, Jane Eyre, aged 10, living with her maternal uncle's family, the Reeds, as a result of her uncle's dying wish. It is several years after her parents died of typhus. Mr. Reed, Jane's uncle, was the only person in the Reed family who was ever kind to Jane. Jane's aunt, Sarah Reed, dislikes her, treats her as a burden, and discourages her children from associating with Jane. Mrs. Reed and her three children are abusive to Jane, physically, emotionally, and spiritually. The nursemaid Bessie proves to be Jane's only ally in the household, even though Bessie sometimes harshly scolds Jane. Excluded from the family activities, Jane is incredibly unhappy, with only a doll and books for comfort.

One day, after her cousin John Reed knocks her down and she attempts to defend herself, Jane is locked in the red room where her uncle died; there, she faints from panic after she thinks she has seen his ghost. She is subsequently attended to by the kindly apothecary Mr. Lloyd to whom Jane reveals how unhappy she is living at Gateshead Hall. He recommends to Mrs. Reed that Jane should be sent to school, an idea Mrs. Reed happily supports. Mrs. Reed then enlists the aid of the harsh Mr. Brocklehurst, director of Lowood Institution, a charity school for girls. Mrs. Reed cautions Mr. Brocklehurst that Jane has a "tendency for deceit", which he interprets as her being a "liar". Before Jane leaves, however, she confronts Mrs. Reed and declares that she'll never call her "aunt" again, that Mrs. Reed and her daughters, Georgiana and Eliza, are the ones who are deceitful, and that she will tell everyone at Lowood how cruelly Mrs. Reed treated her.

Lowood...

At Lowood Institution, a school for poor and orphaned girls, Jane soon finds that life is harsh, but she attempts to fit in and befriends an older girl, Helen Burns, who is able to accept her punishment philosophically. During a school inspection by Mr. Brocklehurst, Jane accidentally breaks her slate, thereby drawing attention to herself. He then stands her on a stool, brands her a liar, and shames her before the entire assembly. Jane is later comforted by her friend, Helen. Miss Temple, the caring superintendent, facilitates Jane's self-defence and writes to Mr. Lloyd, whose reply agrees with Jane's. Jane is then publicly cleared of Mr. Brocklehurst's accusations.

The 80 pupils at Lowood are subjected to cold rooms, poor meals, and thin clothing. Many students fall ill when a typhus epidemic strikes, and Jane's friend Helen dies of consumption in her arms. When Mr. Brocklehurst's maltreatment of the students is discovered, several benefactors erect a new building and install a sympathetic management committee to moderate Mr. Brocklehurst's harsh rule. Conditions at the school then improve dramatically.

The name Lowood symbolizes the "low" point in Jane's life where she was maltreated. Helen Burns is a representation of Charlotte's elder sister Maria, who died of tuberculosis after spending time at a school where the children were mistreated.

Thornfield Hall...

After six years as a student and two as a teacher at Lowood, Jane decides to leave, like her friend and confidante Miss Temple, who recently married. She advertises her services as a governess and receives one reply, from Alice Fairfax, housekeeper at Thornfield Hall. Jane takes the position, teaching Adèle Varens, a young French girl.

One night, while Jane is walking to a nearby town, a horseman passes her. The horse slips on ice and throws the rider. Despite the rider's surliness, Jane helps him to get back onto his horse. Later, back at Thornfield, she learns that this man is Edward Rochester, master of the house. Adèle is his ward, left in his care when her mother abandoned her.

At Jane's first meeting with him within Thornfield, Mr. Rochester teases her, accusing her of bewitching his horse to make him fall. He also talks strangely in other ways, but Jane is able to stand up to his initially arrogant manner. Mr. Rochester and Jane soon come to enjoy each other's company, and spend many evenings together.

Odd things start to happen at the house, such as a strange laugh, a mysterious fire in Mr. Rochester's room (from which Jane saves Rochester by rousing him and throwing water on him and the fire), and an attack on a house guest named Mr. Mason. Then Jane receives word that her aunt Mrs. Reed is calling for her, because she suffered a stroke after her son John died. Jane returns to Gateshead and remains there for a month, attending to her dying aunt. Mrs. Reed confesses to Jane that she wronged her, giving Jane a letter from Jane's paternal uncle, Mr. John Eyre, in which he asks for her to live with him and be his heir. Mrs. Reed admits to telling Mr. Eyre that Jane had died of fever at Lowood. Soon afterward, Mrs. Reed dies, and Jane helps her cousins after the funeral before returning to Thornfield.

Back at Thornfield, Jane broods over Mr. Rochester's rumoured impending marriage to the beautiful and talented, but snobbish and heartless, Blanche Ingram. However, one midsummer evening, Rochester baits Jane by saying how much he will miss her after getting married, but how she will soon forget him. The normally self-controlled Jane reveals her feelings for him. Rochester is then sure that Jane is sincerely in love with him, and he proposes marriage. Jane is at first sceptical of his sincerity, but eventually believes him and gladly agrees to marry him. She then writes to her Uncle John, telling him of her happy news.

As she prepares for her wedding, Jane's forebodings arise when a strange woman sneaks into her room one night and rips her wedding veil in two. As with the previous mysterious events, Mr. Rochester attributes the incident to Grace Poole, one of his servants. During the wedding ceremony, Mr. Mason and a lawyer declare that Mr. Rochester cannot marry because he is already married to Mr. Mason's sister, Bertha. Mr. Rochester admits this is true but explains that his father tricked him into the marriage for her money. Once they were united, he discovered that she was rapidly descending into congenital madness, and so he eventually locked her away in Thornfield, hiring Grace Poole as a nurse to look after her. When Grace gets drunk, Rochester's wife escapes and causes the strange happenings at Thornfield.

It turns out that Jane's uncle, Mr. John Eyre, is a friend of Mr. Mason's and was visited by him soon after Mr. Eyre received Jane's letter about her impending marriage. After the marriage ceremony is broken off, Mr. Rochester asks Jane to go with him to the south of France, and live with him as husband and wife, even though they cannot be married. Refusing to go against her principles, and despite her love for him, Jane leaves Thornfield in the middle of the night.

Other employment...

Jane travels as far from Thornfield as she can using the little money she had previously saved. She accidentally leaves her bundle of possessions on the coach and has to sleep on the moor, and unsuccessfully attempts to trade her handkerchief and gloves for food. Exhausted and hungry, she eventually makes her way to the home of Diana and Mary Rivers, but is turned away by the housekeeper. She collapses on the doorstep, preparing for her death. St. John Rivers, Diana and Mary's brother and a clergyman, saves her. After she regains her health, St. John finds Jane a teaching position at a nearby village school. Jane becomes good friends with the sisters, but St. John remains aloof.

The sisters leave for governess jobs, and St. John becomes somewhat closer to Jane. St. John learns Jane's true identity and astounds her by telling her that her uncle, John Eyre, has died and left her his entire fortune of 20,000 pounds (equivalent to over £1.3 million in 2011. When Jane questions him further, St. John reveals that John Eyre is also his and his sisters' uncle. They had once hoped for a share of the inheritance but were left virtually nothing. Jane, overjoyed by finding that she has living and friendly family members, insists on sharing the money equally with her cousins, and Diana and Mary come back to live at Moor House.

Proposals...

Thinking Jane will make a suitable missionary's wife, St. John asks her to marry him and to go with him to India, not out of love, but out of duty. Jane initially accepts going to India but rejects the marriage proposal, suggesting they travel as brother and sister. As soon as Jane's resolve against marriage to St. John begins to weaken, she mystically hears Mr. Rochester's voice calling her name. Jane then returns to Thornfield to find only blackened ruins. She learns that Mr. Rochester's wife set the house on fire and committed suicide by jumping from the roof. In his rescue attempts, Mr. Rochester lost a hand and his eyesight. Jane reunites with him, but he fears that she will be repulsed by his condition. "Am I hideous, Jane?", he asks. "Very, sir: you always were, you know", she replies. When Jane assures him of her love and tells him that she will never leave him, Mr. Rochester again proposes, and they are married. He eventually recovers enough sight to see their firstborn son.

Monday, December 25, 2017

"A Visit From Saint Nicholas," --- [The complete poem by Clement Clarke Moore, 1837]...

As dry leaves before the wild hurricane fly,

When they met without obstacle, mount to the sky,

So, up to the housetop the reindeer they flew,

With a sleigh full of toys and Saint Nicholas too.

And then, in a twinkling, I heard on the roof,

The prancing and pawing of each tiny hoof.

As I drew in my head and was turning around,

Down the chimney Saint Nicholas came with a bound!

He was dressed all in fur, from his head to his foot,

And, his clothes were all tarnished with ashes and soot.

The stump of a pipe he held tight in his teeth and the smoke

Encircled his head like a wreath.

His eye how they twinkled!

His dimples how merry!

His cheeks were like roses!

His nose like a cherry!

His droll little mouth was drawn up in a bow.

And, the beard on his chin was as white as the snow.

He spoke not a word, but went straight to his work.

He filled every stocking, then turned with a jerk.

And, laying his finger beside his nose and giving a nod

Up the chimney he rose!

He sprang to his sled!

To his team, gave a whistle!

And, away they all flew like the down of a thistle!

But, I heard him exclaim, as he drove out of sight,

"Happy Christmas to all and to all a good night!"

--- Clement Clarke Moore, 1837.

Saturday, December 23, 2017

The Deadly Risks Of A Victorian Beauty Regime...

Thursday, December 21, 2017

Wednesday, December 20, 2017

"The Raven," By Edgar Allen Poe...

The Raven

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

"'Tis some visiter," I muttered, "tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more."

"Not the least obeisance made he", as illustrated by Gustave Doré (1884)

"The Raven" follows an unnamed narrator on a dreary night in December who sits reading "forgotten lore" by a dying fire as a way to forget the death of his beloved Lenore. A "tapping at [his] chamber door"[6] reveals nothing, but excites his soul to "burning". The tapping is repeated, slightly louder, and he realizes it is coming from his window. When he goes to investigate, a raven flutters into his chamber. Paying no attention to the man, the raven perches on a bust of Pallas above the door.

Amused by the raven's comically serious disposition, the man asks that the bird tell him its name. The raven's only answer is "Nevermore". The narrator is surprised that the raven can talk, though at this point it has said nothing further. The narrator remarks to himself that his "friend" the raven will soon fly out of his life, just as "other friends have flown before" along with his previous hopes. As if answering, the raven responds again with "Nevermore".The narrator reasons that the bird learned the word "Nevermore" from some "unhappy master" and that it is the only word it knows.

Even so, the narrator pulls his chair directly in front of the raven, determined to learn more about it. He thinks for a moment in silence, and his mind wanders back to his lost Lenore. He thinks the air grows denser and feels the presence of angels, and wonders if God is sending him a sign that he is to forget Lenore. The bird again replies in the negative, suggesting that he can never be free of his memories. The narrator becomes angry, calling the raven a "thing of evil" and a "prophet".[8] Finally, he asks the raven whether he will be reunited with Lenore in Heaven. When the raven responds with its typical "Nevermore", he is enraged, and, calling it a liar, commands the bird to return to the "Plutonian shore"[8]—but it does not move. Presumably at the time of the poem's recitation by the narrator, the raven "still is sitting"[8] on the bust of Pallas. The narrator's final admission is that his soul is trapped beneath the raven's shadow and shall be lifted "Nevermore".

A Bit Of Info On the Origin Of The Vampire...

A vampire is a being from folklore that subsists by feeding on the life essence (generally in the form of blood) of the living. In European folklore, vampires were undead beings that often visited loved ones and caused mischief or deaths in the neighbourhoods they inhabited when they were alive. They wore shrouds and were often described as bloated and of ruddy or dark countenance, markedly different from today's gaunt, pale vampire which dates from the early 19th century.

Vampiric entities have been recorded in most cultures; the term vampire, previously an arcane subject, was popularised in the West in the early 19th century, after an influx of vampire superstition into Western Europe from areas where vampire legends were frequent, such as the Balkans and Eastern Europe;[1] local variants were also known by different names, such as shtriga in Albania, vrykolakas in Greece and strigoi in Romania. This increased level of vampire superstition in Europe led to mass hysteria and in some cases resulted in corpses being staked and people being accused of vampirism.

In modern times, the vampire is generally held to be a fictitious entity, although belief in similar vampiric creatures such as the chupacabra still persists in some cultures. Early folk belief in vampires has sometimes been ascribed to the ignorance of the body's process of decomposition after death and how people in pre-industrial societies tried to rationalise this, creating the figure of the vampire to explain the mysteries of death. Porphyria was linked with legends of vampirism in 1985 and received much media exposure, but has since been largely discredited.

The charismatic and sophisticated vampire of modern fiction was born in 1819 with the publication of The Vampyre by John Polidori; the story was highly successful and arguably the most influential vampire work of the early 19th century.[4] Bram Stoker's 1897 novel Dracula is remembered as the quintessential vampire novel and provided the basis of the modern vampire legend. The success of this book spawned a distinctive vampire genre, still popular in the 21st century, with books, films, and television shows. The vampire has since become a dominant figure in the horror genre. Anne Rice, author of "The Vampire Chronicles," did a lot to bring about the popularity of the sexy male vampire.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)