Hello. I'm writer Antoinette Beard... WOO-HOO!!!... Here are quirky fascinations of the Victorian to the Edwardian age, and some things that happened later that were just too bizarre to resist... Such a yummy time of quaintness & blossoming industry. Scroll down for a multitude of coolness... Ha-ha-ha, always there are those who flaunt conventions, Darlings... ;)

Friday, August 31, 2018

The Flamboyant P.T. Barnum...

P. T. Barnum was considered the father of modern-day advertising, and one of the most famous showmen/managers of the freak show industry. In the United States he was a major figure in popularizing the entertainment. However, it was very common for Barnum's acts to be schemes and not altogether true. Barnum was fully aware of the improper ethics behind his business as he said, "I don't believe in duping the public, but I believe in first attracting and then pleasing them." During the 1840s Barnum began his museum, which had a constantly rotating acts schedule, which included The Fat Lady, midgets, giants, and other people deemed to be freaks. The museum drew in about 400,000 visitors a year.

P.T. Barnum’s American Museum was one of the most popular museums in New York City to exhibit freaks. In 1841 Barnum purchased The American Museum, which made freaks the major attraction, following mainstream America at the mid-19th century. Barnum was known to advertise aggressively and make up outlandish stories about his exhibits. The façade of the museum was decorated with bright banners showcasing his attractions and included a band that performed outside. Barnum’s American Museum also offered multiple attractions that not only entertained but tried to educate and uplift its working-class visitors. Barnum offered one ticket that guaranteed admission to his lectures, theatrical performances, an animal menagerie, and a glimpse at curiosities both living and dead.

One of Barnum's exhibits centered around Charles Stratton, the dwarf "General Tom Thumb" who was then 4 years of age but was stated to be 11. Charles had stopped growing after the first 6 months of his life, at which point he was 25 inches (64 cm) tall and weighed 15 pounds (6.8 kg). With heavy coaching and natural talent, the boy was taught to imitate people from Hercules to Napoleon. By 5, he was drinking wine, and by 7 smoking cigars for the public's amusement. During 1844–45, Barnum toured with Tom Thumb in Europe and met Queen Victoria, who was amused and saddened by the little man, and the event was a publicity coup. Barnum paid Stratton handsomely - about $150.00 a week. When Stratton retired, he lived in the most esteemed neighborhood of New York, he owned a yacht, and dressed in the nicest clothing he could buy.

In 1860, The American Museum had listed and archived thirteen human curiosities in the museum, including an albino family, The Living Aztecs, three dwarfs, a black mother with two albino children, The Swiss Bearded Lady, The Highland Fat Boys, and What Is It? (Henry Johnson, a mentally disabled black man). Barnum introduced the "man-monkey" William Henry Johnson, a microcephalic black dwarf who spoke a mysterious language created by Barnum. In 1862, he discovered the giantess Anna Swan and Commodore Nutt, a new Tom Thumb, with whom Barnum visited President Abraham Lincoln at the White House. During the Civil War, Barnum's museum drew large audiences seeking diversion from the conflict.

Barnum's most popular and highest grossing act was the Tattooed Man, George Contentenus. He claimed to be a Greek-Albanian prince raised in a Turkish harem. He had 338 tattoos covering his body. Each one was ornate and told a story. His story was that he was on a military expedition but was captured by native people, who gave him the choice of either being chopped up into little pieces or receive full body tattoos. This process supposedly took three months and Contentenus was the only hostage who survived. He produced a 23-page book, which detailed every aspect of his experience and drew a large crowd. When Contentenus partnered with Barnum, he began to earn more than $1,000 a week. His wealth became so staggering that the New York Times wrote, "He wears very handsome diamond rings and other jewelry, valued altogether at about $3,000 [$71,500 in 2014 dollars] and usually goes armed to protect himself from persons who might attempt to rob him." Though Contentenus was very fortunate, other freaks were not. Upon his death in 1891, he donated about half of his life earnings to other freaks who did not make as much money as he did.

One of Barnum's most famous hoaxes was early in his career. He hired a blind and paralyzed former slave for $1,000. He claimed this woman was 160 years old, but she was actually only 80 years old. This lie helped Barnum make a weekly profit of nearly $1,000. This hoax was one of the first, but one of the more convincing.

Barnum retired in 1865 when his museum burnt to the ground.[16] Though Barnum was and still is criticized for exploitation, he paid the performers fairly handsome sums of money. Some of the acts made the equivalent of what some sport stars make today.

The Scandalous Can Can, --- [Occasionally, people were arrested for dancing it.]...

The cancan is believed to have evolved from the final figure in the quadrille, which is a social dance by four couples. The exact origin of the dance is obscure, but the steps may have been inspired by a popular entertainer of the 1820s, Charles Mazurier, well known for his acrobatics, including the grand écart or jump splits — both popular features of the cancan.

The dance was considered scandalous, and for a while, there were attempts to repress it. This may have been partly because in the 19th century, women wore pantalettes, which had an open crotch, meaning that a high kick could be unintentionally revealing. There is no evidence that cancan dancers wore special closed underwear, although it has been claimed that the Moulin Rouge management did not permit dancers to perform in "revealing undergarments". Occasionally, people dancing the cancan were arrested, but there is no record of it being banned, as some accounts claim.

Throughout the 1830s, it was often groups of men, particularly students, who danced the cancan at public dance-halls. As the dance became more popular, professional performers emerged, although it was still danced by individuals, not by a chorus line. A few men became cancan stars in the 1840s to 1861 and an all-male group known as the Quadrille des Clodoches performed in London in 1870. However, women performers were much more widely known. The early cancan dancers were probably prostitutes, but by the 1890s, it was possible to earn a living as a full-time dancer and stars such as La Goulue and Jane Avril emerged, who were highly paid for their appearances at the Moulin Rouge and elsewhere. The most prominent male can-can dancer of the time was Valentin le Désossé (Valentin the Boneless). a frequent partner of La Goulue.

The professional dancers of the Second Empire and the fin de siècle developed the cancan moves that were later incorporated by the choreographer Pierre Sandrini in the spectacular "French Cancan", which he devised at the Moulin Rouge in the 1920s and presented at his own Bal Tabarin from 1928. This was a combination of the individual style of the Parisian dance-halls and the chorus-line style of British and American music halls (see below).

Outside France

In the United States and elsewhere, the can-can achieved popularity in music halls, where it was danced by groups of women in choreographed routines. This style was imported back into France in the 1920s for the benefit of tourists, and the French Cancan was born — a highly choreographed routine lasting ten minutes or more, with the opportunity for individuals to display their "specialities". The main moves are the high kick or battement, the rond de jambe (quick rotary movement of lower leg with knee raised and skirt held up), the port d'armes (turning on one leg, while grasping the other leg by the ankle and holding it almost vertically), the cartwheel and the grand écart (the flying or jump splits). It has become common practice for dancers to scream and yelp while performing the cancan.

The cancan was introduced in America on 23 December 1867 by Giuseppina Morlacchi, dancing as a part of The Devil's Auction at the Theatre Comique in Boston. It was billed as "Grand Gallop Can-Can, composed and danced by Mlles. Morlacchi, Blasina, Diani, Ricci, Baretta...accompanied with cymbals and triangles by the coryphees and corps de ballet." The new dance received an enthusiastic reception.

By the 1890s the cancan was out of style in New York dance halls, having been replaced by the hoochie coochie.

The cancan became popular in Alaska and Yukon, Canada where theatrical performances feature cancan dancers to the present day.

Perception

The cancan is now considered a part of world dance culture. Often the main feature observed today is how physically demanding and tiring the dance is to perform, but it still retains a bawdy, suggestive element.

When the dance first appeared in the early 19th century, it was considered a scandalous dance, similar to how rock and roll was perceived in the 1950s. In the mid-19th century it was thought to be extremely inappropriate by respectable society. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the cancan was viewed as much more erotic because the dancers made use of the extravagant underwear of the period, and the contrasting black stockings. They lifted and manipulated their skirts much more, and incorporated a move sometimes considered the most cheeky and provocative—bending over and throwing their skirts over their backs, presenting their bottoms to the audience. The Moulin Rouge dancer La Goulue was well known for this gesture, and she had a heart embroidered on the seat of her drawers.

A cancan dancer would sometimes stand very close to a man, and bet that she could take off his hat without using her hands. When he took the bet, she would execute a high kick that would take off his hat—and give him a quick look at her pantaloons while she was at it. It was also a warning that anyone taking unwanted liberties with a dancer could expect a kick in the face.

Early editions of The Oxford Companion to Music defined the cancan as "A boisterous and latterly indecorous dance of the quadrille order, exploited in Paris for the benefit of such British and American tourists as will pay well to be well shocked. Its exact nature is unknown to anyone connected with this Companion."

In other art

Many composers have written music for the cancan. The most famous music is French composer Jacques Offenbach's Galop Infernal in his operetta Orphée aux Enfers (Orpheus in the Underworld) (1858).[15] Other examples occur in Franz Lehár's operetta The Merry Widow (1905) and Cole Porter's musical play Can-Can (1954), which in turn formed the basis for the 1960 musical film Can-Can starring Frank Sinatra and Shirley MacLaine. Some other songs that have become associated with the can-can include Aram Khachaturian's "Sabre Dance" from his ballet Gayane (1938) and the music hall standard "Ta-ra-ra Boom-de-ay."

The can-can has often appeared in ballet, most notably Léonide Massine's La Boutique fantasque (1919) and Gaîté Parisienne (1938),[16] as well as The Merry Widow. A particularly fine example can be seen at the climax of Jean Renoir's 1954 film French Cancan.[17] Another well-known can-can is in the "Dance of the Hours" from the opera La Gioconda by Amilcare Ponchielli.

French painter Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec produced several paintings and a large number of posters of can-can dancers. Other painters to have treated the can-can as a subject include Georges Seurat, Georges Rouault, and Pablo Picasso.

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Can-Can Dance, --- From The 1952 Movie "Moulin Rouge"...

Whoever choreographed this had very carefully studied Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec's paintings and drawings of the dancers at the original Moulin Rouge in Paris because many of their moves are exactly as they're shown in his artwork... SENSATIONAL!!!

Wednesday, August 29, 2018

The Victorian Circus & Performers...

The circus is a word which is derived from the Latin term circus which means circle or ring. Circus rose to its popularity in the Victorian period. Circuses were prior to its growth as a commercial form of entertainment, would travel from town to town and showed their acts and tricks in parks or public places.

Victorian era circuses were a part of its culture as it was regarded as a form of entertainment. By the mid-Victorian period, there were numerous circuses which were running their shows in England.

The rise of the circus from mere a performance of artists to being a form of entertainment for the Victorian people was because of its demand. During the Victorian period, only a certain class of society would watch the circus, but after its popularity all the classes watched it.

Common circus acts

The impact of these circuses was so powerful that even the 19th-century theaters included circus acts like jugglers, aerial acts, etc. Trapeze wires were strung from the roofs of these theaters and the artists would show their acts above the crowd of people sitting in the stalls.

The Victorian circuses included skilled artists who performed the dangerous tricks and the basic goal of these circuses was to create excitement amongst the audience. In the event of the circus being in the open air, only a ring of rope was placed on the floor within which the entertainers performed their acts. A wooden barrier was kept from where the audience enjoyed the performances. If the circus was in the evening or night, candles were stacked on the wooden barriers to enable the spectators to watch the circus.

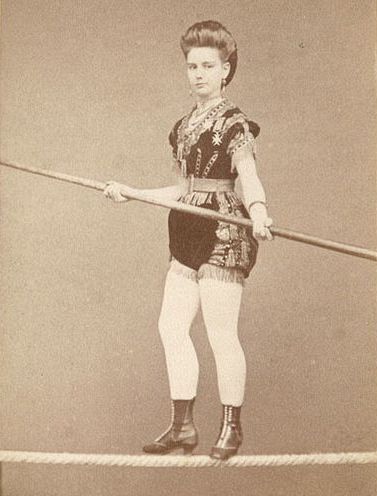

The earliest circuses which operated in Britain comprised of small groups of entertainers which performed their acts and were normally seen at fairs. This small troupe of artists included an equestrian clown, a tightrope walker, and a couple of horses which helped in pulling the wagon when these artists would be traveling.

The circus during the Victorian period would include a performance of artists of an actual battle scene, Chinese jugglers, clowns, female acrobats and even child performers. The trick riding was an important performance which was a part of every circus which operated in Britain and the other acts changed from circus to circus. The aquatic circus was one of the acts developed during this time.

In this act, the circus ring would be flooded with water. However, although these acts provided the audience with entertainment, it should be taken into account that the performances acted out by the performers were extremely dangerous. The famous circus proprietors during the Victorian period were Banister and West, Price and Powell, Abraham Saunders, Lord George Sanger, Frederick Charles Hengler, etc.

The Industrial Revolution of the 19th century brought along new inventions and developments which proved to be very useful to the circuses. With the help of these inventions, the circuses in Victorian England could develop new skills and techniques which mesmerized the audiences.

One of the key factors that helped circus become so appreciated was the fact that the entertainers or artists who performed at these circuses traveled from place to place for their audience, even if it was the smallest town. This touring circus was also known as Tenting circus, which became popular in the 19th century.

The circuses with a large number of artists were known to announce their arrival in a town with the help of circus parade which was successful in drawing the attention of a larger population.

With the growth of railways, these performers were able to travel to the remotest areas which were earlier cut-off from the rest of the places. Thus, it can be seen that the circus which began as an act performed only in fairs became a popular form of commercial entertainment for the people during the 19th century.

Here are some more circus images:

Le Chat Noir, --- "The Black Cat Cafe" In Bohemian Montmartre, Paris...

Le Chat Noir (French for "The Black Cat") was a nineteenth-century entertainment establishment, in the bohemian Montmartre district of Paris. It opened on 18 November 1881 at 84 Boulevard de Rochechouart by the impresario Rodolphe Salis, and closed in 1897 not long after Salis' death.

Le Chat Noir is thought to be the first modern cabaret:[ a nightclub where the patrons sat at tables and drank alcoholic beverages while being entertained by a variety show on stage. The acts were introduced by a master of ceremonies who interacted with well-known patrons at the tables. Its imitators have included cabarets from St. Petersburg (Stray Dog Café) to Barcelona (Els Quatre Gats).

Perhaps best known now by its iconic Théophile Steinlen poster art, in its heyday it was a bustling nightclub that was part artist salon, part rowdy music hall. From 1892 to 1895 the cabaret published a weekly magazine with the same name, featuring literary writings, news from the cabaret and Montmartre, poetry, and political satire.

The cabaret began by renting the cheapest accommodations it could find, a small two-room site located at 84 Boulevard Rochechouart, (now commemorated only by a historical plaque). Its success was assured with the wholesale arrival of a group of radical young writers and artists called Les Hydropathes ("those who are afraid of water – so they drink only wine"), a club led by the journalist Émile Goudeau. The group claimed to be averse to water, preferring wine and beer. Their name doubled as a nod to the "rabid" zeal with which they advocated their sociopolitical and aesthetic agendas. Goudeau’s club met in his house on the Rive Gauche (left bank), but had become so popular that it outgrew its meeting place. Salis met Goudeau, whom he convinced to relocate the club meeting place across the river on rue de Laval (now rue Victor-Massé).

Second site

Le Chat Noir soon outgrew its first site. In June 1885, three and a half years after opening, it moved to larger accommodations at 12 Rue Victor-Massé. The new venue was the sumptuous old private mansion of the painter Alfred Stevens, who, at Salis' request, transformed it into a "fashionable country inn" with the help of the architect Maurice Isabey. On 10 June 1885, with great fanfare, Salis moved to new premises at 12 Rue Victor-Massé.

Soon, a growing crowd of poets and singers gathered at Le Chat Noir, which offered an ideal venue and opportunity to practice their acts before fellow performers, guests and colleagues.

With exaggerated, ironic politeness, Salis most often played the role of conférencier (post-performance lecturer, or master of ceremonies). It was here that the Salon des Arts Incohérents (Salon of Incoherent Arts), shadow plays, and comic monologues got their start.

Famous men and women to patronize the Chat Noir included Jane Avril, Franc-Nohain, Adolphe Willette, Caran d'Ache, André Gill, Émile Cohl, Paul Bilhaud, Sarah England, Paul Verlaine, Henri Rivière, Claude Debussy, Erik Satie, Charles Cros, Jules Laforgue, Yvette Guilbert, Charles Moréas, Albert Samain, Louis Le Cardonnel, Coquelin Cadet, Emile Goudeau, Alphonse Allais, Maurice Rollinat, Maurice Donnay, Armand Masson, Aristide Bruant, Théodore Botrel, Paul Signac, Porfirio Pires, August Strindberg, George Auriol, Marie Krysinska, and Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec.

The last shadow play by Salis's company was staged in January 1897, after which Salis took the company on tour. Salis was talking of plans to move the cabaret to a location in Paris itself, but he died on 19 March 1897.

The death of Rodophe Salis in 1897 spelled the end of the Chat Noir. By that time, the fascination for Montmartre had already diminished, and Salis had already disposed of many of the club’s assets and facilities. Soon after Salis’ death, the artists dispersed, and Le Chat Noir slowly disappeared.

Last location

Ten years later, in 1907, Jehan Chargot opened an eponymous café in an effort to resurrect, modernize, and continue the work of his illustrious predecessor. This new Chat Noir, located at 68, boulevard de Clichy, remained popular into the 1920s.

Today, a neon sign which incorporates Steinlen’s iconic Chat Noir image is on display at 68, Boulevard de Clichy, now the site of a hotel by the same name.

Other cabarets successfully copied and adapted the model established by the Chat Noir. In December 1899, Henri Fursy opened his Boîte à Fursy cabaret in the former Chat Noir hôtel on rue Victor-Massé. He claimed to have inherited the mantle of Salis, and said his cabaret "has thanks to Fursy become once again the goal of all who 'climb Montmartre' to hear their favorite chansonniers..."

Shadow play

Under the management of Rodolphe Salis, Le Chat noir produced 45 théatre d'ombres (shadow play) shows between 1885 and 1896, as the art became more popular in Europe. Behind a screen on the second floor of the establishment, the artist Henri Rivière worked with up to 20 assistants in a large, oxy-hydrogen backlit performance area and used a double optical lantern to project backgrounds. Figures were originally cardboard cutouts, but zinc figures were used after 1887. Various artists took part in the creation, including Steinlen, Adolphe Willette and Albert Robida. Caran d'Ache designed around 50 cutouts for the very popular 1888 show L'Epopée.

Cultural associations]

A poster of "Le Chat Noir" may be seen prominently in the crime scene photographs from the 2001 murder of Kathleen Peterson by her husband and novelist Michael Peterson. Le Chat Noir is the name of the nightclub where Frank Sinatra and Natalie Wood rekindle their relationship, in the 1958 movie Kings Go Forth. There is also the famous cat painting with blinking eyes on the entrance wall.

Tuesday, August 28, 2018

John Huston, 1952: " Moulin Rouge"...

Jose Ferrer is so wonderful in this classic; he won the oscar for best actor --- and then there's the Can-Can & Zsa Zsa Gabor as Jane Avril. It also has one of my favorite songs, --- "Where Is Your Heart?".

Monday, August 27, 2018

Those Raucous & Scandalous Music Halls...

Origins and development

Music hall in London had its origins in the 18th century. It grew with the entertainment provided in the new style saloon bars of public houses during the 1830s. These venues replaced earlier semi-rural amusements provided by fairs and suburban pleasure gardens such as Vauxhall Gardens and the Cremorne Gardens. These latter became subject to urban development and became fewer and less popular.

The saloon was a room where for an admission fee or a greater price at the bar, singing, dancing, drama or comedy was performed. The most famous London saloon of the early days was the Grecian Saloon, established in 1825, at The Eagle (a former tea-garden), 2 Shepherdess Walk, off the City Road in east London.[10] According to John Hollingshead, proprietor of the Gaiety Theatre, London (originally the Strand Music Hall), this establishment was "the father and mother, the dry and wet nurse of the Music Hall". Later known as the Grecian Theatre, it was here that Marie Lloyd made her début at the age of 14 in 1884. It is still famous because of an English nursery rhyme, with the somewhat mysterious lyrics:

The interior of Wilton's (here, being set for a wedding). The lines of tables give some idea of how early music halls were used as supper clubs.

Another famous "song and supper" room of this period was Evans Music-and-Supper Rooms, 43 King Street, Covent Garden, established in the 1840s by W.H. Evans. This venue was also known as 'Evans Late Joys' – Joy being the name of the previous owner. Other song and supper rooms included the Coal Hole in The Strand, the Cyder Cellars in Maiden Lane, Covent Garden and the Mogul Saloon in Drury Lane.

The music hall as we know it developed from such establishments during the 1850s and were built in and on the grounds of public houses. Such establishments were distinguished from theatres by the fact that in a music hall you would be seated at a table in the auditorium and could drink alcohol and smoke tobacco whilst watching the show. In a theatre, by contrast, the audience was seated in stalls and there was a separate bar-room. An exception to this rule was the Britannia Theatre, Hoxton (1841) which somehow managed to evade this regulation and served drinks to its customers. Though a theatre rather than a music hall, this establishment later hosted music hall variety acts.

Early music halls

The establishment often regarded as the first true music hall was the Canterbury, 143 Westminster Bridge Road, Lambeth built by Charles Morton, afterwards dubbed "the Father of the Halls", on the site of a skittle alley next to his pub, the Canterbury Tavern. It opened on 17 May 1852 and was described by the musician and author Benny Green as being "the most significant date in all the history of music hall". The hall looked like most contemporary pub concert rooms, but its replacement in 1854 was of then unprecedented size. It was further extended in 1859, later rebuilt as a variety theatre and finally destroyed by German bombing in 1942.

Another early music hall was The Middlesex, Drury Lane (1851). Popularly known as the 'Old Mo', it was built on the site of the Mogul Saloon. Later converted into a theatre it was demolished in 1965. The New London Theatre stands on its site.

Several large music halls were built in the East End. These included the London Music Hall, otherwise known as The Shoreditch Empire, 95–99 Shoreditch High Street, (1856–1935). This theatre was rebuilt during 1894 by Frank Matcham, the architect of the Hackney Empire. Another in this area was the Royal Cambridge Music Hall, 136 Commercial Street (1864–1936). Designed by William Finch Hill (the designer of the Britannia theatre in nearby Hoxton), it was rebuilt after a fire in 1898.

The construction of Weston's Music Hall, High Holborn (1857), built up on the site of the Six Cans and Punch Bowl Tavern by the licensed victualler of the premises, Henry Weston, signalled that the West End was fruitful territory for the music hall. During 1906 it was rebuilt as a variety theatre and renamed as the Holborn Empire. It was closed as a result of German action in the Blitz on the night of 11–12 May 1941 and the building was pulled down in 1960. Significant West End music halls include:

- The Oxford Music Hall, 14/16 Oxford Street (1861) – built on the site of an old coaching inn called the Boar and Castle by Charles Morton, the pioneer music hall developer of The Canterbury, who with this development brought music hall to the West End. Demolished in 1926.

- The London Pavilion (1861). Facade of 1885 rebuild still extant.

- The Alhambra, Leicester Square (1860), in the former premises of the London Panopticon. This sophisticated venue was noted for its alluring corps de ballet and was a focal point for West End pleasure seekers. It was demolished in 1936.

Other large suburban music halls included:

- The Old Bedford, 93–95 High Street, Camden Town (1861). Built on the site of the tea gardens of a pub called the Bedford Arms. The Bedford was a favourite haunt of the artists known as the Camden Town Group headed by Walter Sickert, who featured interior scenes of music halls in his paintings, including one entitled 'Little Dot Hetherington at The Old Bedford'. The Old Bedford was demolished in 1969.

- Collins', Islington Green (1862). Opened by Sam Collins, in 1862, as the Lansdowne Music Hall, converting the pre-existing Lansdowne Arms public house, it was renamed as Collins' Music Hall in 1863. It was colloquially known as 'The Chapel on the Green'. Collins was a star of his own theatre, singing mostly Irish songs specially composed for him. It closed in 1956, after a fire, but the street front of the building still survives (see below).

- Deacons in Clerkenwell (1862).

A noted music hall entrepreneur of this time was Carlo Gatti who built a music hall, known as Gatti's, at Hungerford Market in 1857. He sold the music hall to South Eastern Railway in 1862, and the site became Charing Cross railway station. With the proceeds from selling his first music hall, Gatti acquired a restaurant in Westminster Bridge Road, opposite The Canterbury music hall. He converted the restaurant into a second Gatti's music hall, known as "Gatti's-in-the-Road", in 1865. It later became a cinema. The building was badly damaged in the Second World War, and was demolished in 1950. In 1867, he acquired a public house in Villiers Street named "The Arches", under the arches of the elevated railway line leading to Charing Cross station. He opened it as another music hall, known as "Gatti's-in-The-Arches". After his death his family continued to operate the music hall, known for a period as the Hungerford or Gatti's Hungerford Palace of Varieties.

It became a cinema in 1910, and the Players' Theatre in 1946.

By 1865, there were 32 music halls in London seating between 500 and 5,000 people plus an unknown, but large, number of smaller venues.

In 1878, numbers peaked, with 78 large music halls in the metropolis and 300 smaller venues. Thereafter numbers declined due to stricter licensing restrictions imposed by the Metropolitan Board of Works and LCC, and because of commercial competition between popular large suburban halls and the smaller venues, which put the latter out of business.

Variety theatre

A new era of variety theatre was developed by the rebuilding of the London Pavilion in 1885. Contemporary accounts noted:

Hitherto the halls had borne unmistakeable evidence of their origins, but the last vestiges of their old connections were now thrown aside, and they emerged in all the splendour of their new-born glory. The highest efforts of the architect, the designer and the decorator were enlisted in their service, and the gaudy and tawdry music hall of the past gave way to the resplendent "theatre of varieties" of the present day, with its classic exterior of marble and freestone, its lavishly appointed auditorium and its elegant and luxurious foyers and promenades brilliantly illuminated by myriad electric lights— Charles Stuart and A. J. Park The Variety Stage (1895)

One of the most famous of these new palaces of pleasure in the West End was the Empire, Leicester Square, built as a theatre in 1884 but acquiring a music hall licence in 1887. Like the nearby Alhambra this theatre appealed to the men of leisure by featuring alluring ballet dancers and had a notorious promenade which was the resort of courtesans. Another spectacular example of the new variety theatre was the Tivoli in the Strand built 1888–90 in an eclectic neo-Romanesque style with Baroque and Moorish-Indian embellishments. "The Tivoli" became a brand name for music-halls all over the British Empire.[26] During 1892, the Royal English Opera House, which had been a financial failure in Shaftesbury Avenue, applied for a music hall licence and was converted by Walter Emden into a grand music hall and renamed the Palace Theatre of Varieties, managed by Charles Morton. Denied by the newly created LCC permission to construct the promenade, which was such a popular feature of the Empire and Alhambra, the Palace compensated in the way of adult entertainment by featuring apparently nude women in tableaux vivants, though the concerned LCC hastened to reassure patrons that the girls who featured in these displays were actually wearing flesh-toned body stockings and were not naked at all.

One of the grandest of these new halls was the Coliseum Theatre built by Oswald Stoll in 1904 at the bottom of St Martin's Lane. This was followed by the London Palladium (1910) in Little Argyll Street.

Both were designed by the prolific Frank Matcham. As music hall grew in popularity and respectability, and as the licensing authorities exercised ever firmer regulation,[31] the original arrangement of a large hall with tables at which drink was served, changed to that of a drink-free auditorium. The acceptance of music hall as a legitimate cultural form was established by the first Royal Variety Performance before King George V during 1912 at the Palace Theatre. However, consistent with this new respectability the best-known music hall entertainer of the time, Marie Lloyd, was not invited, being deemed too "saucy" for presentation to the monarchy.

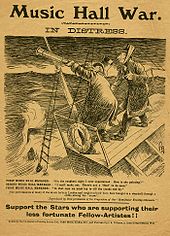

'Music Hall War' of 1907

The development of syndicates controlling a number of theatres, such as the Stoll circuit, increased tensions between employees and employers. On 22 January 1907, a dispute between artists, stage hands and managers of the Holborn Empire worsened. Strikes in other London and suburban halls followed, organised by the Variety Artistes' Federation. The strike lasted for almost two weeks and was known as the Music Hall War.[33] It became extremely well known, and was advocated enthusiastically by the main spokesmen of the trade union and Labour movement – Ben Tillett and Keir Hardie for example. Picket lines were organized outside the theatres by the artistes, while in the provinces theatre management attempted to oblige artistes to sign a document promising never to join a trade union.

The strike ended in arbitration, which satisfied most of the main demands, including a minimum wage and maximum working week for musicians.

Several music hall entertainers such as Marie Dainton, Marie Lloyd, Arthur Roberts, Joe Elvin and Gus Elen were strong advocates of the strike, though they themselves earned enough not to be concerned personally in a material sense. Lloyd explained her advocacy:

We (the stars) can dictate our own terms. We are fighting not for ourselves, but for the poorer members of the profession, earning thirty shillings to £3 a week. For this they have to do double turns, and now matinées have been added as well. These poor things have been compelled to submit to unfair terms of employment, and I mean to back up the federation in whatever steps are taken.— Marie Lloyd, on the Music Hall War.

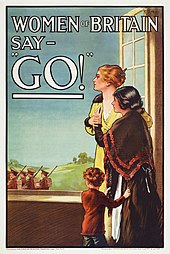

Recruiting

World War I may have been the high-water mark of music hall popularity. The artists and composers threw themselves into rallying public support and enthusiasm for the war effort. Patriotic music hall compositions such as "Keep the Home Fires Burning" , "Pack up Your Troubles", "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" and "We Don't Want to Lose You (but we think you ought to Go)", were sung by music hall audiences, and sometimes by soldiers in the trenches.

Many songs promoted recruitment ("All the boys in khaki get the nice girls", 1915); others satirised particular elements of the war experience. "What did you do in the Great war, Daddy" criticised profiteers and slackers; Vesta Tilley's "I've got a bit of a blighty one" showed a soldier delighted to have a wound just serious enough to be sent home. The rhymes give a sense of grim humour (When they wipe my face with sponges / and they feed me on blancmanges / I'm glad I've got a bit of a blighty one).

Tilley became more popular than ever during this time, when she and her husband, Walter de Frece, managed a military recruitment drive. In the guise of characters like 'Tommy in the Trench' and 'Jack Tar Home from Sea', Tilley performed songs such as "The army of today's all right" and "Jolly Good Luck to the Girl who Loves a Soldier". This is how she got the nickname Britain's best recruiting sergeant – young men were sometimes asked to join the army on stage during her show. She also performed in hospitals and sold war bonds. Her husband was knighted in 1919 for his own services to the war effort, and Tilley became Lady de Frece.

Once the reality of war began to sink home, the recruiting songs all but disappeared – the Greatest Hits collection for 1915 published by top music publisher Francis and Day contains no recruitment songs. After conscription was brought in 1916, songs dealing with the war spoke mostly of the desire to return home. Many also expressed anxiety about the new roles women were taking in society.

Decline

Music hall continued during the interwar period, but no longer as the single dominant form of popular entertainment in Britain. The improvement of cinema, the development of radio, and the cheapening of the gramophone damaged its popularity greatly. It now had to compete with jazz, swing and big band dance music. Licensing restrictions also changed its character.

In 1914, the London County Council (LCC) enacted that drinking be banished from the auditorium into a separate bar and during 1923 even the separate bar was abolished by parliamentary decree. The exemption of the theatres from this latter act prompted some critics to denounce this legislation as an attempt to deprive the working classes of their pleasures, as a form of social control, whilst sparing the supposedly more responsible upper classes who patronised the theatres (though this could be due to the licensing restrictions brought about due to the Defence of the Realm Act 1914, which also applied to public houses as well). Even so, the music hall gave rise to such major stars as George Formby, Gracie Fields, Max Miller, Will Hay, and Flanagan and Allen during this period.

In the early 1950s, rock and roll, whose performers initially topped music hall bills, attracted a young audience who had little interest in the music hall acts while driving the older audience away. The final demise was competition from television, which grew very popular after the Queen's coronation was televised. Some music halls tried to retain an audience by putting on striptease acts. In 1957, the playwright John Osborne delivered this elegy:

The music hall is dying, and with it, a significant part of England. Some of the heart of England has gone; something that once belonged to everyone, for this was truly a folk art.— John Osbourne, The Entertainer (1957)

Moss Empires, the largest British music hall chain, closed the majority of its theatres in 1960, closely followed by the death of music hall stalwart Max Miller in 1963, prompting one contemporary to write that: "Music-halls ... died this afternoon when they buried Max Miller". Miller himself had sometimes said that the genre would die with him. Many music hall performers, unable to find work, fell into poverty; some did not even have a home, having spent their working lives living in digs between performances.

Stage and film musicals, however, continued to be influenced by the music hall idiom, including Oliver!, Dr Dolittle and My Fair Lady. The BBC series The Good Old Days, which ran for thirty years, recreated the music hall for the modern audience, and the Paul Daniels Magic Show allowed several speciality acts a television presence from 1979 to 1994. Aimed at a younger audience, but still owing a lot to the music hall heritage, was the late '70s series The Muppet Show.

Music halls of Paris

The music hall was first imported into France in its British form in 1862, but under the French law protecting the state theatres, performers could not wear costumes or recite dialogue, something only allowed in theaters. When the law changed in 1867, the Paris music hall flourished, and a half-dozen new halls opened, offering acrobats, singers, dancers, magicians, and trained animals. The first Paris music call built specially for that purpose was the Folies-Bergere (1869); it was followed by the Moulin Rouge(1889), the Alhambra (1866), the first to be called a music hall, and the Olympia (1893). The Printania (1903) was a music-garden, open only in summer, with a theater, restaurant, circus, and horse-racing. Older theaters also transformed themselves into music halls, including the Bobino (1873), the Bataclan (1864), and the Alcazar (1858). At the beginning, music halls offered dance reviews, theater and songs, but gradually songs and singers became the main attraction.

Paris music halls all faced stiff competition in the interwar period from the most popular new form of entertainment, the cinema. They responded by offering more complex and lavish shows. In 1911, the Olympia had introduced the giant stairway as a set for its productions, an idea copied by other music halls. The singer Mistinguett made her debut the Casino de Paris in 1895 and continued to appear regularly in the 1920s and 1930s at the Folies Bergère, Moulin Rouge and Eldorado. Her risqué routines captivated Paris, and she became one of the most highly-paid and popular French entertainers of her time.

One of the most popular entertainers in Paris during the period was the American singer Josephine Baker. Baker sailed to Paris, France. She first arrived in Paris in 1925 to perform in a show called "La Revue Nègre" at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. ]She became an immediate success for her erotic dancing, and for appearing practically nude on stage. After a successful tour of Europe, she returned to France to star at the Folies Bergère. Baker performed the 'Danse sauvage,' wearing a costume consisting of a skirt made of a string of artificial bananas.

The music-halls suffered growing hardships in the 1930s. The Olympia was converted into a movie theater, and others closed. Others continued to thrive. In 1937 and 1930, the Casino de Paris presented shows with Maurice Chevalier, who had already achieved success as an actor and singer in Hollywood.

In 1935, a twenty-year old singer named Édith Piaf was discovered in the Pigalle by nightclub owner Louis Leplée, whose club, Le Gerny, off the Champs-Élysées, was frequented by the upper and lower classes alike. He persuaded her to sing despite her extreme nervousness. Leplée taught her the basics of stage presence and told her to wear a black dress, which became her trademark apparel. Leplée ran an intense publicity campaign leading up to her opening night, attracting the presence of many celebrities, including Maurice Chevalier. Her nightclub appearance led to her first two records produced that same year, and the beginning of a legendary career.

Competition from movies and television largely brought an end to the Paris music hall. However, a few still flourish, with tourists as their primary audience. Major music halls include the Folies-Bergere, Crazy Horse Saloon, Casino de Paris, Olympia, and Moulin Rouge.

History of the songs

The musical forms most associated with music hall evolved in part from traditional folk song and songs written for popular drama, becoming by the 1850s a distinct musical style. Subject matter became more contemporary and humorous, and accompaniment was provided by larger house-orchestras as increasing affluence gave the lower classes more access to commercial entertainment and to a wider range of musical instruments, including the piano. The consequent change in musical taste from traditional to more professional forms of entertainment arose in response to the rapid industrialisation and urbanisation of previously rural populations during the Industrial Revolution. The newly created urban communities, cut off from their cultural roots, required new and readily accessible forms of entertainment.

Music halls were originally tavern rooms which provided entertainment, in the form of music and speciality acts, for their patrons. By the middle years of the nineteenth century, the first purpose-built music halls were being built in London. The halls created a demand for new and catchy popular songs that could no longer be met from the traditional folk song repertoire. Professional songwriters were enlisted to fill the gap.

The emergence of a distinct music hall style can be credited to a fusion of musical influences. Music hall songs needed to gain and hold the attention of an often jaded and unruly urban audience. In America, from the 1840s, Stephen Foster had reinvigorated folk song with the admixture of Negro spiritual to produce a new type of popular song. Songs like "Old Folks at Home" (1851) and "Oh, Dem Golden Slippers" spread round the globe, taking with them the idiom and appurtenances of the minstrel song. Other influences on the rapidly developing music hall idiom were Irish and European music, particularly the jig, polka, and waltz.

Typically, a music hall song consists of a series of verses sung by the performer alone, and a repeated chorus which carries the principal melody, and in which the audience is encouraged to join.

In Britain, the first music hall songs often promoted the alcoholic wares of the owners of the halls in which they were performed. Songs like "Glorious Beer", and the first major music hall success, Champagne Charlie (1867) had a major influence in establishing the new art form. The tune of "Champagne Charlie" became used for the Salvation Army hymn "Bless His Name, He Sets Me Free" (1881). When asked why the tune should be used like this, William Booth is said to have replied "Why should the devil have all the good tunes? "The people the Army sought to save, knew nothing of the hymn tunes or gospel melodies used in the churches, but 'the music hall had been their melody school.'"

By the 1870s, the songs were free of their folk music origins, and particular songs also started to become associated with particular singers, often with exclusive contracts with the songwriter, just as many pop songs are today. Towards the end of the style the music became influenced by ragtime and jazz, before being overtaken by them.

Music hall songs were often composed with their working class audiences in mind. Songs like "My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)'", "Knocked 'em in the Old Kent Road", and Waiting at the Church expressed in melodic form situations with which the urban poor were very familiar. Music hall songs could be romantic, patriotic, humorous or sentimental, as the need arose. The most popular music hall songs became the basis for the pub songs of the typical Cockney "knees up".

Although a number of songs show a sharply ironic and knowing view of working class life, there were, too, those which were repetitive, derivative, written quickly and sung to make a living rather than a work of art.

Famous music hall songs

- "Any Old Iron" (Charles Collins; Terry Sheppard) sung by Harry Champion.

- "Belgium Put the Kibosh on the Kaiser" (Alf Ellerton) sung by Mark Sheridan.

- "Boiled Beef and Carrots" (Charles Collins and Fred Murray) sung by Harry Champion.

- "The Boy I Love is Up in the Gallery" (George Ware) sung by Nelly Power, and Marie Lloyd.

- "Burlington Bertie from Bow" (William Hargreaves) sung by Ella Shields.

- "Daddy Wouldn't Buy Me a Bow Wow" (Joseph Tabrar) sung by Vesta Victoria.

- "Daisy Bell (Bicycle Built for Two)" (Harry Dacre) sung by Katie Lawrence.

- "Down at the Old Bull and Bush" (Harry von Tilzer; Andrew B. Sterling) sung by Florrie Forde.

- "Every Little Movement Has a Meaning Of Its Own" (J. C. Moore; Fred E. Cliffe) sung by Marie Lloyd; superior U.K. take on "Every Little Movement (Has a Meaning All Its Own)".

- "Good-bye-ee!" (R. P. Weston; Bert Lee) sung by Florrie Forde and Daisy Wood.

- "Has Anybody Here Seen Kelly?" (C. W. Murphy and Will Letters) sung by Florrie Forde.

- "Hello, Hello, Who's Your Lady Friend?" (Harry Fragson; Worton David; Bert Lee) sung by Mark Sheridan.

- "Hold Your Hand Out, Naughty Boy" (C. W. Murphy and Will Letters) sung by Florrie Forde.

- "I Belong to Glasgow", written and performed by Will Fyffe.

- "I Do Like to Be Beside the Seaside" (John A. Glover-Kind) sung by Mark Sheridan.

- "I Was A Good Little Girl" (Clifford F. Harris; James W. Tate) sung by Clarice Mayne and That.

- "If It Wasn't For The 'Ouses In Between" (George Le Brunn; Edgar Bateman) sung by Gus Elen.

- "I'm Henery the Eighth, I Am" (1911) (Fred Murray and Bert Weston) sung by Harry Champion.

- "It's a Bit of a Ruin That Cromwell Knocked About a Bit" (Harry Bedford; Terry Sullivan) sung by Marie Lloyd.

- "It's a Long Way to Tipperary" (1914) (Jack Judge and Harry Williams) sung by John McCormack.

- "Let's All Go Down the Strand" (Harry Castling and C. W. Murphy) sung by Charles R. Whittle.

- "Lily of Laguna" (Leslie Stuart) sung by Eugene Stratton, and later G. H. Elliott.

- "[[The Daring Young Man on the Flying Trapeze|The Man on the Flying Trapeze" (George Leybourne; Gaston Lyle; arr. Alfred Lee) sung by George Leybourne.

- "The Man Who Broke the Bank at Monte Carlo" (Fred Gilbert) sung by Charles Coborn.

- "My Old Dutch" (Albert Chevalier; Charles Ingle) sung by Albert Chevalier.

- "My Old Man (Said Follow the Van)" (Charles Collins and Fred W. Leigh) sung by Marie Lloyd.

- "Nellie Dean" (Henry W. Armstrong) sung by Gertie Gitana.

- "Oh, It's a Lovely War" (J. P. Long; Maurice Scott) sung by Ella Shields.

- "Oh! Mr Porter" (George Le Brunn and Thomas Le Brunn) sung by Marie Lloyd, and Norah Blaney.

- "Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag" (Felix Powell) sung by Florrie Forde.

- "Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ay" (Harry J. Sayers) sung by Lottie Collins.

- "Waiting at the Church" (Henry E. Pether; Frank W. Leigh) sung by Vesta Victoria.

- "Where Did You Get That Hat?" (Joseph J. Sullivan, 1888; words rewritten 1901 by James Rolmaz[54]) sung by J. C. Heffron (1857-1934)

- "Who Were You With Last Night?" (Fred Godfrey; Mark Sheridan) sung by Mark Sheridan.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)